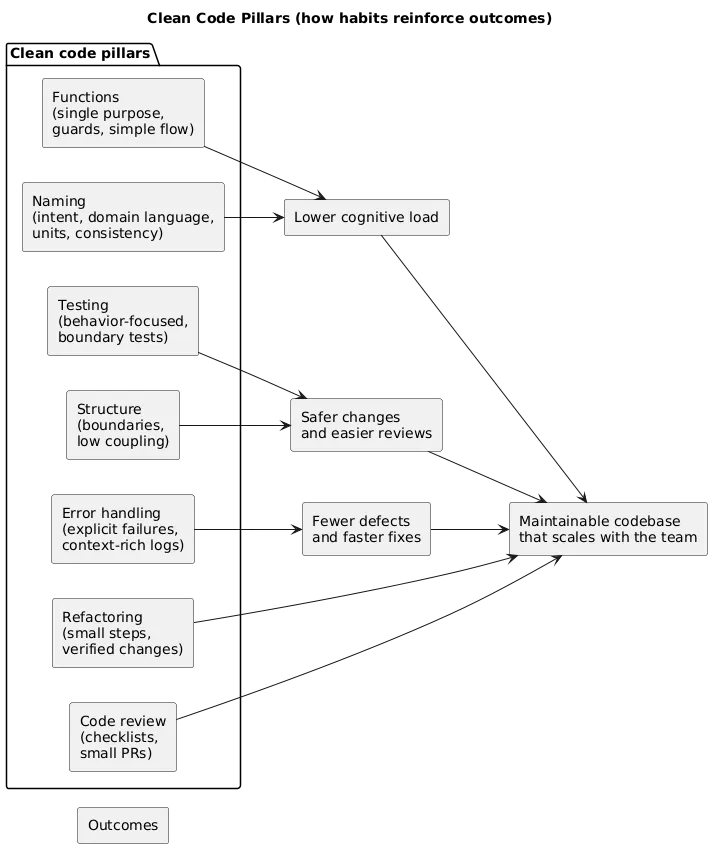

Clean code is code that is easy to read, change, and review. In practice, it means reducing cognitive load: clear naming, small focused functions, explicit boundaries, and predictable behavior — supported by tests and incremental refactoring.

This guide is intentionally practical: what to do, what to avoid, and how to apply clean code principles without turning them into rigid rules or unnecessary abstraction.

Practical definition

If a teammate can safely change the code without fear, and can explain what it does after a quick read, it’s probably clean enough.

1. What “Clean Code” Means (In Practice)

“Clean” does not mean “perfect”. It means the codebase stays predictable as it grows: changes don’t ripple everywhere, production defects are easier to diagnose, and new contributors can ramp up quickly.

- Readable: intent is obvious from names and structure.

- Changeable: features can be added without chaos.

- Testable: logic can be validated without fragile setups.

- Reviewable: diffs are small and easy to reason about.

A realistic goal

Most teams aim for code that is “boring to maintain”. If the next engineer can make a change without needing a deep mental model of the entire system, you’re winning.

If you want a broader process view (planning → delivery → maintenance), see the SDLC guide: Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) Explained .

2. Naming: The Highest-ROI Clean Code Habit

Good names reduce the need for comments, prevent misunderstandings, and speed up reviews. They also make refactoring safer because you can confidently search and reason about behavior.

Naming checklist (quick wins)

- Use domain language: reflect business concepts (Invoice, Subscription, Refund).

- Name by intent: what it means, not how it’s stored (emailAddress vs emailString).

- Include units: timeoutMs, priceCents, sizeBytes.

- Make booleans readable: isEnabled, hasAccess, shouldRetry.

- Be consistent: one concept, one word across the codebase.

Naming smell

If a variable needs a long comment to explain it, the name is probably wrong — or the responsibility is unclear.

| Situation | Weak name | Better name | Why it’s better |

|---|---|---|---|

| User permissions | flag | hasBillingAccess | Conveys meaning and usage |

| Collections | list | pendingInvoices | Explains what’s inside |

| Time values | timeout | requestTimeoutMs | Clarifies scope + unit |

| Business rules | calc() | calculateRenewalPrice() | Indicates purpose and domain |

Common naming traps

- Noise words: manager, helper, data (unless they truly add meaning).

- Abbreviations: they scale poorly across teams unless standardized.

- Overly generic names: process(), handle(), doWork() hide intent.

- Inconsistent synonyms: customer vs client vs user for the same concept.

3. Functions: Single Purpose, Simple Control Flow

Clean functions are easy to explain. They do one thing, keep control flow simple, and make edge cases explicit.

- Do one thing: single responsibility per function.

- Keep them short: long functions hide bugs and edge cases.

- Reduce nesting: guard clauses beat deep if/else pyramids.

- Limit parameters: too many args signals missing abstraction.

- Prefer pure logic: separate computation from I/O when possible.

Guard clauses (a readability multiplier)

If a function has multiple prerequisites, check them early and exit. This keeps the “happy path” visible and reduces indentation.

// Conceptual pattern (language-agnostic)

function processOrder(order):

if order is null: return error

if order is not payable: return error

if payment provider unavailable: return retry

// happy path continues hereCommand/Query separation (practical version)

- Queries return data and do not mutate state.

- Commands perform actions/mutations and return a result/status.

4. Structure: Modules, Boundaries, and Separation of Concerns

Clean code scales when responsibilities are separated and dependency direction is intentional. Most “messy codebases” suffer from unclear boundaries more than from imperfect naming.

Common boundaries that keep software maintainable:

- UI vs logic: keep rendering separate from business rules.

- Domain vs infrastructure: isolate DB/API details behind interfaces/adapters.

- Public vs internal APIs: make the safe path obvious for other developers.

- Feature boundaries: group code by feature when it reduces cross-module coupling.

Boundary test

If changing one feature forces edits in many unrelated places, the boundary is wrong. Move code until “change happens in one place”.

5. Comments: When They Help (And When They Hurt)

Comments are not “bad”. But they are a maintenance cost: they can drift out of date and become misinformation. Use comments when they add durable context.

- Good comments: explain intent, trade-offs, constraints, links to decisions.

- Bad comments: restate the code, narrate obvious steps, duplicate names.

- Best outcome: refactor so the comment becomes unnecessary.

Comment rule

Comment “why”, not “what”. The code should already communicate “what”.

Useful comment patterns

- Intent: why a “weird” approach is used (performance, compatibility, limitations).

- Constraints: business rules or compliance restrictions that future refactors must respect.

- Decision records: short references to ADRs or tickets for deep context.

- TODOs with owner and date: avoid permanent TODOs that nobody owns.

6. Error Handling: Fail Fast, Fail Clearly

Error handling is where many codebases get noisy: inconsistent exceptions, vague messages, and logs with no context. Clean code treats failures as first-class behavior.

- Validate inputs early: fail fast with clear messages.

- Handle expected failures: retries, fallbacks, user messaging, and timeouts.

- Keep errors actionable: include relevant identifiers, not just “something went wrong”.

- Log with context: correlation IDs, request IDs, and key metadata.

- Standardize error shapes: consistent error contracts simplify handling.

Anti-pattern

Catch-all exception blocks that hide the original cause (or log without context) often increase MTTR.

7. Tests: Confidence, Not Coverage Theater

The goal of tests is confidence: you can change code and ship safely. “High coverage” can still produce fragile tests that break every refactor, slowing development down.

A practical testing strategy

| Layer | What it protects | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Unit tests | Core business logic | Fast feedback; encourages clean design |

| Integration tests | Boundaries (DB, API, queues) | Catches contract mismatches and configuration issues |

| E2E tests | Critical user flows | Validates real behavior but is slower and more brittle |

- Test behavior: outcomes, not internal implementation details.

- Use clear structure: Arrange / Act / Assert is readable across languages.

- Prefer simple fixtures: minimize setup to reduce brittleness.

- Mock with restraint: too much mocking often signals tight coupling.

Fragile tests

If tests break every refactor, they are testing internals instead of behavior. Refactor tests along with code.

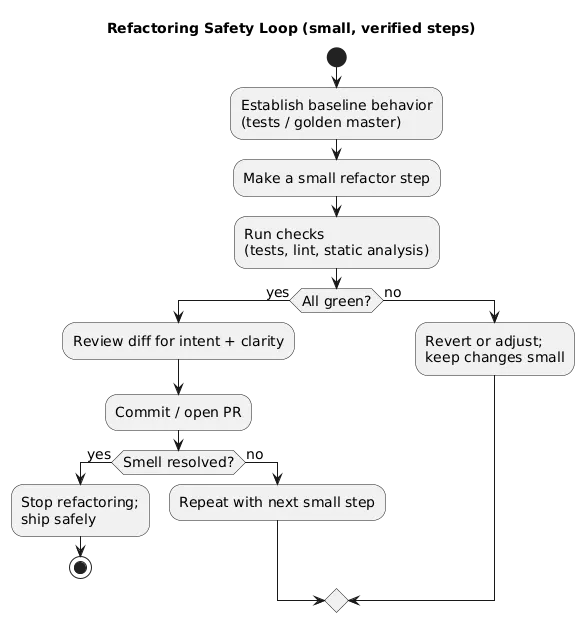

8. Refactoring Workflow: Improve Code Without Breaking It

Refactoring is how you keep a codebase healthy. The key is to do it safely: small steps, protected by tests, and reviewed like any other change.

A safe refactoring loop:

- Establish behavior (tests, snapshot, or “golden master” if legacy).

- Refactor in small steps (tiny commits or PRs).

- Run checks (tests, linting, static analysis).

- Review diff for clarity, risk, and unintended changes.

- Repeat until the smell is gone — not until the code is “perfect”.

When to refactor (pragmatic guidance)

- High-churn areas: code you touch often should be easy to change.

- Bug magnets: modules that cause incidents usually need simplification.

- Duplication: repeated logic is a long-term defect multiplier.

- Before adding features: refactor just enough to make the new work clean.

9. SOLID Essentials (Without Over-Engineering)

SOLID is best used as a toolbox, not a religion. Apply principles when they reduce coupling, improve testability, or clarify responsibility boundaries.

- S: one reason to change per module/component.

- O: extend behavior without rewriting core logic.

- L: substitutable implementations (avoid surprising overrides).

- I: small interfaces over “god” interfaces.

- D: depend on abstractions at boundaries.

Reality check

If SOLID adds layers but does not reduce risk or improve clarity, it’s over-engineering. Prefer the simplest design that stays flexible.

10. Code Smells and Anti-Patterns to Avoid

A “code smell” is a symptom that often indicates deeper design problems. Smells are not errors by themselves, but they predict future cost.

| Smell | Typical risk | Practical fix |

|---|---|---|

| Long functions | Hidden edge cases, duplication, hard reviews | Extract helpers, guard clauses, clarify intent |

| Large modules/classes | Unclear responsibility, ripple effects | Split by responsibility / feature boundary |

| Duplication | Inconsistent behavior, defects multiply | Extract shared logic; centralize rules |

| Shotgun surgery | One change requires edits everywhere | Move behavior closer to data; improve boundaries |

| Primitive obsession | Rules spread across codebase | Create small domain types/value objects |

| Too many conditionals | Complexity, missed states | Model state; use polymorphism/strategies |

| Tight coupling | Hard tests, hard refactors | Introduce seams at boundaries (interfaces/adapters) |

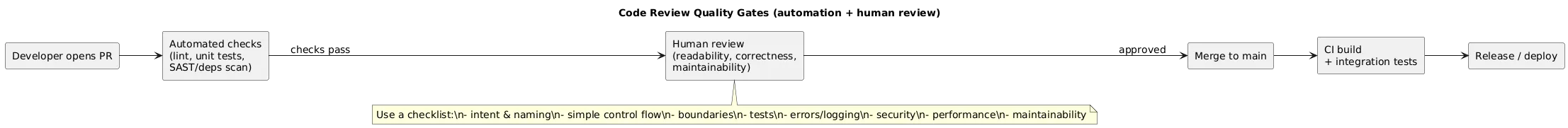

11. Code Review Checklist (Copy/Paste)

Reviews are where clean code becomes a team habit. The best reviews are predictable: a shared checklist, small PRs, and a culture that prioritizes clarity over cleverness.

- Correctness: does it meet requirements and edge cases?

- Readability: clear names, small functions, minimal nesting?

- Tests: new behavior covered, fragile tests avoided?

- Error handling: failures explicit and logged appropriately?

- Security: input validation, auth checks, secrets handling?

- Performance: obvious hotspots avoided, no unnecessary work?

- Maintainability: boundaries respected, duplication reduced?

Copy/paste PR checklist

- [ ] Names communicate intent (domain language, units, boolean clarity)

- [ ] Functions are small and focused; control flow is readable

- [ ] No obvious duplication; responsibilities are well-bounded

- [ ] Errors are explicit; logs contain actionable context

- [ ] Tests protect behavior; boundary tests added where needed

- [ ] No sensitive data in logs; security checks considered

- [ ] PR scope is tight (reviewable in ~15–30 minutes)12. FAQ: Clean Code

Is clean code always the most efficient code?

Not always. Optimize readability first, then optimize performance when profiling shows it matters. Clean code often makes performance work safer because the intent is clearer and tests are stronger.

How do I know what to refactor?

Refactor where change happens frequently: duplicated logic, unclear boundaries, long functions, and modules that are hard to test. If a file is a “bug magnet”, it’s a refactoring candidate.

What’s a reasonable standard for “small functions”?

If you can’t describe a function in one sentence, it likely does too much. Keep it focused and extract helpers for sub-steps.

Do I need strict SOLID everywhere?

No. Use SOLID selectively to reduce coupling and keep critical paths testable. Avoid adding layers that don’t solve a real problem.

What’s the fastest clean code win for teams?

Enforce consistent formatting, agree on naming conventions, and adopt a simple code review checklist. Those three improvements immediately reduce cognitive load across the team.

Key terms (quick glossary)

- Cognitive load

- The mental effort required to understand code. Clean code reduces this.

- Code smell

- A symptom that often indicates deeper design issues (e.g., long functions, duplication).

- Refactoring

- Improving internal code structure without changing external behavior.

- Single Responsibility

- A principle that a component should have one reason to change.

- SOLID

- A set of principles for maintainable OO design (best used as a toolbox).

- Coupling

- How strongly components depend on each other; lower coupling is safer.

- Cohesion

- How well a module’s contents belong together; higher cohesion is better.

- Guard clause

- An early return that prevents deep nesting and clarifies intent.

- Idempotency

- Repeated execution produces the same result (important in retries and distributed systems).

- Cyclomatic complexity

- A measure of branching complexity; high values often correlate with bugs and hard testing.

Worth reading

Recommended guides from the category.