If you’ve ever joined a software project that felt chaotic — unclear requirements, last-minute changes, bugs everywhere — you’ve experienced what happens when there’s no clear Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC).

SDLC is simply a structured way to build software: from the first idea, through planning and coding, all the way to deployment and long-term maintenance. The goal is not “more process”. The goal is repeatable delivery with fewer surprises.

What you’ll be able to do after reading

- Explain the SDLC phases in plain English (and what each phase actually produces).

- Choose an SDLC model that fits your project (Waterfall vs Agile vs V-Model vs hybrid).

- Spot common SDLC failure modes early (requirements churn, weak testing, risky releases).

- Apply SDLC in modern teams using CI/CD, DevOps, and practical quality gates.

1. What is the Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC)?

The Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) is a sequence of stages that a software product goes through from idea to retirement. It answers questions like:

- How do we decide what to build — and how do we know it’s valuable?

- How do we design and implement it so it’s maintainable, secure, and scalable?

- How do we test, release, operate, and improve it over time?

Instead of treating software development as one big “coding phase”, SDLC encourages you to think in clear, repeatable steps. That makes it easier to estimate work, manage risk, and keep quality high.

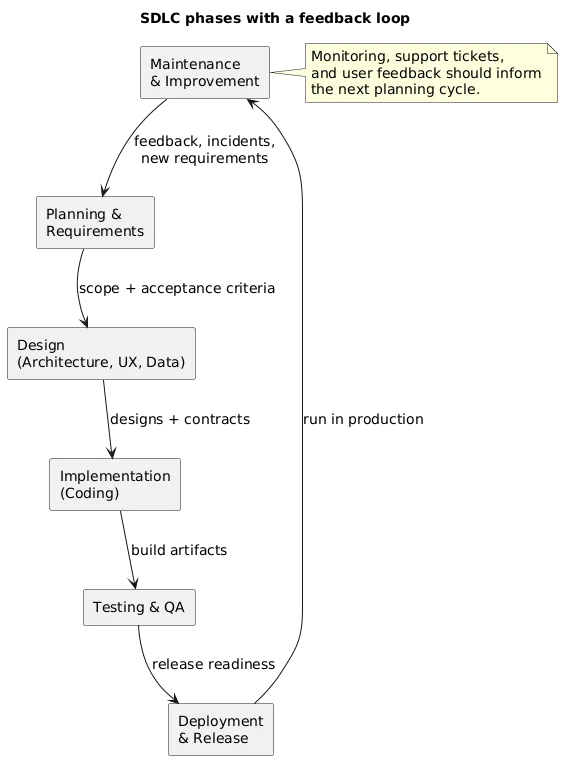

A simple way to remember SDLC

Most SDLCs are a loop: Plan → Design → Build → Test → Release → Operate → Learn → (back to Plan). The faster you learn, the more reliably you improve.

2. Why SDLC matters — even for small teams

You might think SDLC is only for big enterprises, but the core ideas help anyone building software:

- Clarity: everyone knows what stage the work is in and what “done” means.

- Risk management: you identify technical, business, and legal risks early (when they’re cheaper).

- Quality: testing and reviews are part of the workflow, not a last-minute scramble.

- Predictability: stakeholders get realistic timelines and costs based on what’s actually involved.

- Maintainability: you design for change instead of accidentally creating a fragile codebase.

Even a one-person side project benefits from a lightweight SDLC: a bit of planning, a small set of requirements, and an intentional approach to testing and releases.

3. The classic SDLC phases at a glance

Different books label phases differently, but most SDLCs include:

- Planning & requirements

- System & software design

- Implementation (coding)

- Testing & quality assurance

- Deployment & release

- Maintenance & continuous improvement

In older, Waterfall-style projects these phases are mostly sequential. In modern Agile and DevOps teams you still use the phases, but you move through them in short iterations.

4. SDLC deliverables: what you produce in each phase

A common SDLC misunderstanding is thinking the output is “code”. In practice, each phase produces artefacts that reduce risk and make work predictable (even if they are lightweight).

Rule of thumb

If a deliverable doesn’t help someone make a decision, verify quality, or operate the system later, it’s probably noise. Aim for useful, minimal, and maintained artefacts.

| SDLC phase | Typical deliverables | Why it matters |

|---|---|---|

| Planning & requirements | Problem statement, success metrics, scope, user stories/spec, risks, priorities | Aligns expectations and prevents building the wrong thing |

| Design | Architecture diagram, data model, API contracts, UX flows, threat model (optional) | Reduces technical risk before you invest heavily in code |

| Implementation | Code, code reviews, unit/integration tests, developer notes | Makes changes auditable and safer to evolve |

| Testing & QA | Test plan, automated test suites, QA sign-off, defect reports | Catches defects early and prevents regressions |

| Deployment & release | CI/CD pipeline, release notes, rollout plan, rollback plan | Turns releases into routine operations instead of high-risk events |

| Maintenance | Monitoring dashboards, incident playbooks, postmortems, backlog of improvements | Keeps the product healthy and improves reliability over time |

5. Phase 1: Planning & requirements

This phase answers: “Why are we building this, and for whom?” Good planning is not bureaucracy — it’s the cheapest place to fix misunderstandings.

Typical activities include:

- Understanding the problem: what pain points or opportunities are we addressing?

- Identifying stakeholders: users, buyers, support teams, compliance, security.

- Gathering requirements: features, business rules, constraints, acceptance criteria.

- Prioritising: what is “must-have” vs “nice-to-have”?

- Defining success: metrics like conversion, time saved, error reduction, or revenue.

- Rough estimation: cost, timeline, skills, dependencies, and major risks.

Real-life example

A company wants a customer portal. Planning clarifies what customers must do (view invoices, manage profiles, open support tickets), what systems must integrate (billing, CRM), and what “success” means (fewer support calls, faster payments, higher retention).

Requirements that actually work

The best requirements are clear, testable, and prioritised. For example, a good user story includes:

- Who: the user or persona

- Need: what they want to achieve

- Value: why it matters

- Acceptance criteria: how you know it’s done (testable statements)

6. Phase 2: System & software design

Once you know what you’re building, you decide how it should work. Design is where you make the highest-impact trade-offs: scalability, security, cost, and complexity.

In this phase you typically:

- Define architecture: monolith vs microservices, boundaries, databases, APIs.

- Create data models: entities, relationships, and lifecycle of key data.

- Design interfaces: wireframes, user flows, interaction diagrams.

- Choose technologies: frameworks, cloud services, third-party integrations.

- Plan non-functional requirements: performance, reliability, security, compliance.

Design tip

For most projects, one clear architecture diagram + one data flow diagram is worth more than a long document. Keep it updated and use it to onboard new contributors.

7. Phase 3: Implementation (coding)

This is where ideas and diagrams become real code. In a healthy SDLC, coding is connected to requirements and quality gates — not a separate universe.

Good implementation practices include:

- Version control: Git + pull requests for review and traceability.

- Coding standards: consistent patterns make maintenance cheaper.

- Automated tests: unit tests and integration tests alongside the code.

- Small batch changes: smaller PRs are easier to review and less risky to ship.

- Secure defaults: input validation, secrets management, least privilege, dependency hygiene.

Pro tip

Treat tests as part of implementation, not a separate “QA step”. They make refactoring safer and reduce regression risk.

8. Phase 4: Testing & quality assurance

Testing ensures the software behaves as expected and is safe to release. It’s more than “clicking around the app”. Strong SDLCs use a testing strategy, not random testing.

Common types of testing:

- Unit testing: functions/classes in isolation.

- Integration testing: services and components working together.

- End-to-end (E2E) testing: real user flows across the system.

- Performance & load testing: behaviour under expected and peak usage.

- Security testing: vulnerability scanning and misconfiguration checks.

- Accessibility testing: making sure the UI works for diverse users.

Mature teams combine automated testing with code reviews, QA feedback, and targeted exploratory testing where automation is weak.

9. Phase 5: Deployment & release

Deployment is how your software moves from development to a place where real users can access it. A well-run SDLC makes deployment repeatable and boring — which is a compliment.

Key considerations include:

- Environment strategy: dev, test, staging, production (and why each exists).

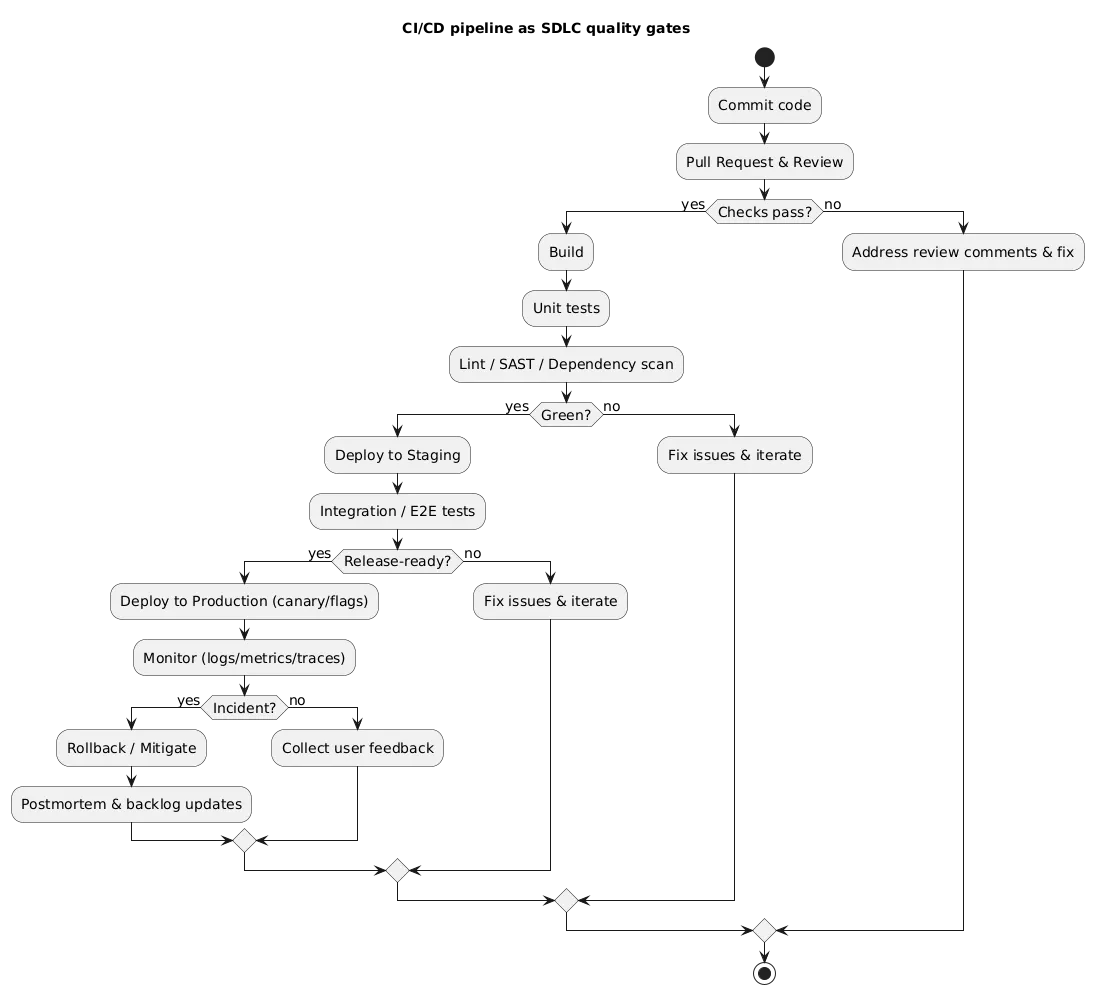

- Automation: CI/CD pipelines to build, test, and deploy reliably.

- Release strategies: blue–green, canary, feature flags, staged rollouts.

- Rollback plans: how you recover quickly if the release breaks something.

- Observability: logs, metrics, traces, and alerting — so you see issues early.

Watch out

A release without monitoring or rollback is a gamble. Make sure you can detect errors quickly — and revert safely if needed.

10. Phase 6: Maintenance & continuous improvement

After release, SDLC doesn’t end. Most of a product’s lifetime is spent in maintenance. This is where teams either build trust with users — or slowly lose it.

Typical maintenance activities:

- Fixing bugs: issues reported by users or detected by monitoring.

- Handling change requests: enhancements and new features.

- Updating dependencies: security patches, framework upgrades, platform changes.

- Reducing technical debt: refactoring, simplification, improving test coverage.

- Incident response: triage, mitigation, postmortems, and prevention work.

A healthy SDLC includes feedback loops from production back into planning and design, so the product keeps evolving instead of decaying.

Practical maintenance metrics (what teams often track)

- Defect escape rate: bugs found in production vs earlier environments.

- Change failure rate: how often releases cause incidents or rollbacks.

- MTTR: mean time to recover from incidents.

- Lead time: how long it takes to ship a change from idea to production.

11. Popular SDLC models: Waterfall, Agile, V-Model & more

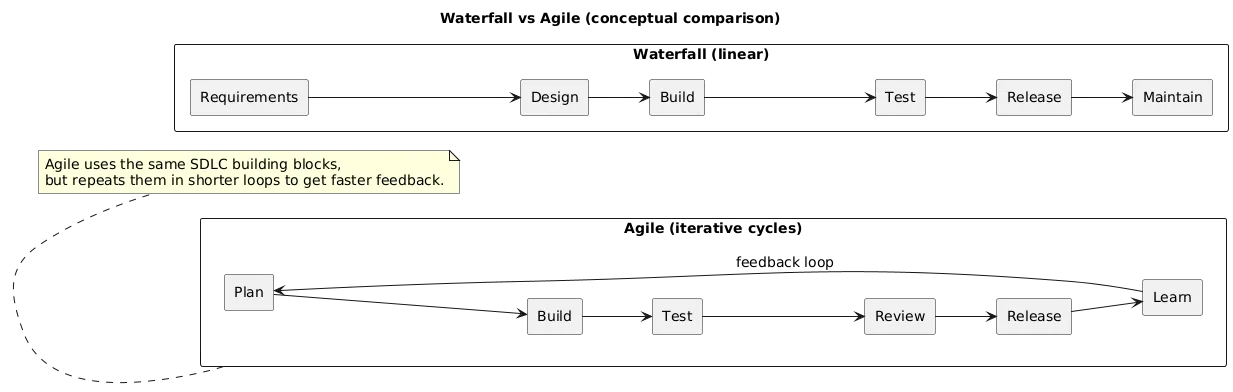

SDLC phases are the what. SDLC models are the how — ways of organising those phases. Most real organisations use a hybrid, but understanding the pure models helps you make trade-offs.

- Waterfall: mostly linear sequence. Best for stable requirements and strong regulation, where extensive upfront documentation is required.

- V-Model: pairs each development phase with a corresponding testing phase. Common in regulated domains where verification and validation must be explicit.

- Iterative / incremental: build in cycles, delivering usable increments over time.

- Agile: short iterations, frequent feedback, and adaptability. Still uses SDLC phases, but in smaller loops.

- Spiral: emphasises risk analysis and iterative refinement for complex/high-risk systems.

How to choose a model quickly

- If requirements are stable and audits matter: Waterfall or V-Model (or a hybrid with strong documentation).

- If requirements evolve and feedback is key: Agile/iterative with tight CI/CD.

- If the system is high-risk or highly uncertain: risk-driven iterations (Spiral concepts) plus prototypes.

12. SDLC in Agile & DevOps teams

In modern teams, SDLC is implemented inside Agile frameworks (Scrum, Kanban) and combined with DevOps practices. The big change is how much is automated and how fast the feedback loop runs.

In practice, that usually means:

- Short cycles: planning → design → build → test in 1–4 week iterations.

- Continuous integration: frequent merges with automated builds and tests.

- Continuous delivery/deployment: small releases that reduce risk.

- Shared ownership: dev, QA, and ops collaborate across the entire lifecycle.

- Shift-left quality: testing and security checks happen earlier, not after deployment.

What “good” looks like

A change is merged only if it passes automated checks (tests, linting, dependency scanning). It is deployed to staging automatically, tested again, then released using a safe rollout strategy (canary/feature flag). Monitoring confirms health — and learnings update the backlog.

13. Common SDLC mistakes & how to avoid them

These pitfalls show up again and again in real projects:

- Skipping requirements: jumping into coding without clarifying goals leads to rework. Fix: write small, testable acceptance criteria.

- Under-investing in testing: QA as a last-minute event. Fix: automate core flows and treat tests as part of the feature.

- Over- or under-documenting: endless docs nobody reads, or none at all. Fix: keep a minimal set of living docs that help decisions and operations.

- Ignoring maintenance: no budget for upgrades or tech debt. Fix: reserve capacity each iteration for reliability and cleanup.

- Tool obsession: believing a new tool will fix process issues. Fix: define outcomes (quality, speed, reliability), then choose tools to support them.

14. Adapting SDLC for small teams & side projects

If you’re solo or in a tiny team, you don’t need a heavyweight SDLC — but you do need structure. The goal is to avoid chaos without adding overhead that kills momentum.

A lightweight SDLC for small projects might look like:

- Planning: a short README with users, goals, and a prioritized feature list.

- Design: one architecture diagram + a note on the data model.

- Implementation: small PRs, a basic test suite, and consistent conventions.

- Testing: a short release checklist (manual + automated).

- Deployment: a repeatable script or CI job.

- Maintenance: a backlog for bugs, upgrades, and refactoring.

Side project success tip

The fastest way to keep a side project alive is to make releases easy. If shipping feels painful, you will avoid it — and the project will stall.

15. SDLC checklists & templates you can copy

Planning checklist

- Problem statement and target users

- Success metrics (how you’ll know it worked)

- Top risks (technical, business, legal/security)

- Prioritized scope (must/should/could)

- Acceptance criteria for the next release

Design checklist

- Architecture diagram (major components + data stores)

- Key data model (entities and relationships)

- API contracts (inputs/outputs, errors, auth)

- Non-functional requirements (performance, security, reliability)

- Operational concerns (logging, monitoring, backups)

Release checklist

- Automated tests green + critical flows verified

- Security checks completed (dependency scan, secrets check)

- Rollback plan prepared

- Release notes written (what changed, what to watch)

- Monitoring/alerts confirmed for critical metrics

16. Frequently asked questions about SDLC

What is SDLC in one sentence?

SDLC is a structured process describing how software moves from idea to a running, maintained product through phases like planning, design, implementation, testing, deployment, and maintenance.

Is SDLC only for big organisations?

No. Big organisations often have more formal processes, but the same ideas help small teams ship higher quality software with fewer surprises.

What’s the difference between SDLC and Agile?

SDLC describes the phases a product goes through. Agile describes how teams organise work within those phases, typically using short iterations and frequent feedback.

How much documentation do I need?

It depends on your domain. Regulated industries need more. Most teams succeed with concise, targeted documentation: requirements, a few diagrams, test strategy, and basic operational notes. Prioritise useful, maintained docs.

How do I start improving my SDLC today?

Pick the biggest pain point (unclear requirements, weak testing, risky releases) and improve that first with a simple template or checklist. Then review each release and iterate.

Key SDLC & software terms (quick glossary)

- SDLC (Software Development Life Cycle)

- The end-to-end process of planning, designing, building, testing, releasing, and maintaining software.

- Requirement

- A description of what the software should do or how it should behave, often written from the user or business perspective.

- Acceptance criteria

- Testable statements that define what “done” means for a feature or user story.

- Architecture

- The high-level structure of a software system and how its components interact (services, databases, APIs, frontends).

- QA (Quality Assurance)

- Practices aimed at ensuring software meets quality standards, including testing, reviews, and process improvement.

- CI/CD (Continuous Integration / Continuous Delivery)

- Practices and tools that automatically build, test, and deploy code changes, enabling frequent and reliable releases.

- Release

- A specific version of software that is packaged and made available to users or customers.

- Rollback

- Reverting to a previous stable version when a new release causes issues.

- Technical debt

- The implied cost of shortcuts or missing improvements that make future changes harder or riskier.

- Stakeholder

- Anyone with an interest in the software: users, customers, managers, support teams, regulators, and more.

- DevOps

- A culture and set of practices bringing development and operations closer, emphasising automation, collaboration, and continuous delivery.

- DevSecOps

- Extending DevOps with security practices integrated into the development and delivery pipeline.

Worth reading

Recommended guides from the category.