Android development is easiest to learn when you focus on the repeatable fundamentals: how the project is built (Gradle), how UI is rendered (Jetpack Compose), how state flows through screens (ViewModel + Flow), and how the app integrates with the OS (permissions, storage, networking, background work).

This guide is modern Android-first for 2025: Kotlin-first and Compose-first. You will still encounter legacy XML in real codebases, but Compose gives beginners a clearer mental model: UI is a function of state.

Beginner outcomes (what you’ll be able to do)

- Set up Android Studio + Emulator and run the same app on a real phone.

- Understand app structure: modules, Gradle, Manifest, resources.

- Build Compose screens and navigation with predictable state.

- Persist data using the right tool (DataStore / Room) and survive restarts.

- Make one API request with good UX (loading + retry + offline behavior).

- Generate a signed release App Bundle (AAB) and prepare a Play Store listing.

1. What Android Development Covers in 2025

Most Android apps are a combination of UI, state, data, and integration points. In 2025, a typical “starter stack” looks like: Kotlin + Jetpack Compose + ViewModel + Room/DataStore + Retrofit.

- Language: Kotlin (default for new apps).

- UI: Jetpack Compose (declarative UI).

- State: ViewModel + Flow (reactive updates).

- Data: DataStore (preferences) + Room (database) + files (as needed).

- Networking: HTTP APIs with robust error handling.

- Build & release: Gradle, signing, App Bundles (AAB).

A realistic first app

Build a 3-screen app: List → Details → Settings. Persist a list locally and (optionally) fetch one dataset from an API. This teaches navigation, state, storage, and networking—without exploding scope.

2. Tools & Setup: Android Studio, SDK, Emulator, Device

A minimal setup is straightforward, but beginners lose time when they skip the “run on a real device” milestone. Treat device testing as part of setup, not a bonus.

- Android Studio: IDE, Compose previews, profiler, emulator tooling.

- Android SDK: platform tools + build tools.

- Emulator: fast iteration; also test on a real phone.

- Real device: the most reliable check for performance and permissions.

- Git: version control from day one.

Real-device check

Emulators are great, but not perfect. Always verify the core user journey on a physical device before you call a feature “done”.

Setup checklist (fast, practical)

- Create a new Compose project and run it on an emulator.

- Enable developer options + USB debugging on your phone and run it there too.

- Commit the initial working project to Git (so you can always roll back).

- Note any SDK/emulator issues you hit—those solutions are reusable across projects.

3. Project Structure: Modules, Gradle, Manifest

Android projects feel “bigger” than they are because they include build configuration, resources, and packaging rules. Once you know where things live, you stop fighting the tooling.

- app module: your app code and resources.

- Gradle files: dependencies, build types, flavors, compile/target versions.

- AndroidManifest.xml: metadata, components, permissions, intent filters.

- resources: strings, icons, themes, translations, layouts (if used).

Build types you will actually use

| Build type | Use case | What changes |

|---|---|---|

| debug | Day-to-day development | Debuggable, often more logging, faster iteration |

| release | Shipping and realistic performance checks | Signed, optimized, fewer logs, different behavior than debug |

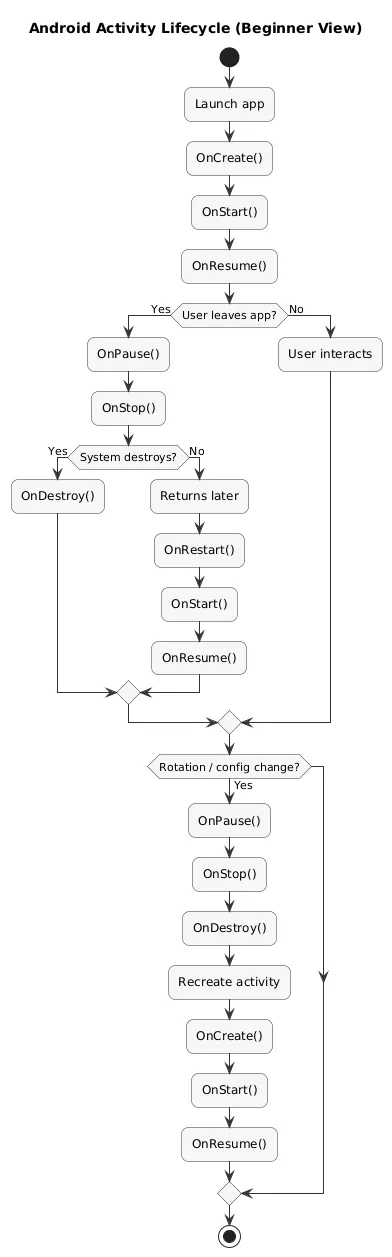

4. Activity Lifecycle & Configuration Changes

The Android lifecycle is not “just theory”—it explains real bugs: lost state on rotation, duplicated network calls, or screens that reset unexpectedly. The key is to know what typically causes a recreate and where state should live.

Lifecycle overview (diagram)

Beginner rule

UI state that must survive rotations and process death should not live only in a composable. Store durable state in a ViewModel and persist what truly matters (Room/DataStore).

5. Kotlin Basics You Actually Need

You do not need all of Kotlin before building apps. You need a practical subset that appears everywhere: null safety, data classes, sealed types, coroutines, and basic collections.

- Null safety: nullable types and safe calls reduce crashes.

- Data classes: clean models for UI and API payloads.

- Sealed classes: expressive UI states and one-off events.

- Coroutines: async work without blocking the main thread.

- Collections: filter/map/grouping show up in UI lists constantly.

// Common UI state pattern (conceptual)

sealed class UiState {

object Idle : UiState()

object Loading : UiState()

data class Success(val items: List<Item>) : UiState()

data class Error(val message: String) : UiState()

}6. Jetpack Compose Fundamentals (UI + Layout)

Compose is declarative: you describe what the UI should look like for a given state, and Compose updates the UI when state changes. This makes UI easier to reason about—if you keep composables small and state predictable.

Compose building blocks you should master first

- Basic layout: Column, Row, Box; spacing and alignment.

- Lists: LazyColumn and stable item keys (for smooth updates).

- Material components: TextField, Button, Card, Scaffold.

- Previews: render Loading/Error/Empty states quickly.

- State hoisting: pass state in, emit events out.

Compose quality bar

Every screen that loads data should explicitly handle: loading, empty, and error. This single habit makes beginner apps feel dramatically more professional.

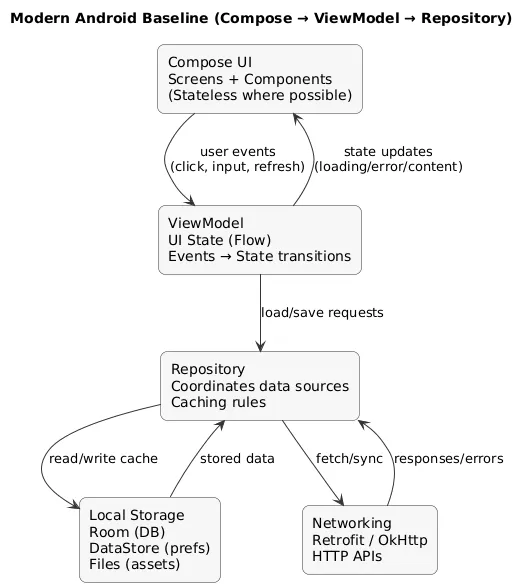

7. State & Architecture: UI → ViewModel → Repository

Beginner apps become messy when networking/storage logic leaks into composables. A simple boundary keeps code readable and testable:

- Compose UI: renders state and sends user intent (events).

- ViewModel: owns state transitions and business rules.

- Repository/services: handle data sources (Room/DataStore/network).

Architecture diagram (recommended baseline)

Avoid this beginner trap

Do not run Retrofit calls inside composables. Trigger work via ViewModel, model state transitions explicitly, and keep UI pure.

8. Navigation: Back Stack, Arguments, Deep Links

Navigation problems are usually state problems in disguise. Keep routes simple, pass stable identifiers, and model one screen as one destination.

- Routes: names for destinations (e.g., "list", "details/{id}").

- Back stack: confirm the Back button behavior early.

- Arguments: pass IDs, not large objects.

- Deep links: add later when you truly need shareable entry points.

Beginner navigation pattern

Build list → details first. Only then add create/edit flows. This prevents you from building complex navigation before the core UX is solid.

9. Permissions & Privacy (Play Store-friendly)

Permissions are both a technical feature and a trust decision. Users (and reviewers) respond better when your app requests only what it needs, exactly when the feature is used.

Permission best practices

- Ask only when needed: do not request “just in case” on first launch.

- Explain the user benefit: tell users what they gain.

- Degrade gracefully: if possible, the app should still work without the permission.

- Minimize scope: extra permissions create friction and can complicate store disclosures.

10. Storage: DataStore vs Room vs Files

Storage choice depends on data shape. Beginners should pick the simplest tool that fits the requirement: preferences/settings are not a database; lists you query usually want a database.

Quick selection table

| Storage | Best for | Common mistakes |

|---|---|---|

| DataStore | Settings, small preferences, flags | Using it for large lists or “searchable items” |

| Room | Structured lists, queries, offline-first | Over-modeling relationships too early |

| Files | Exports, cached media/assets | Doing heavy I/O on main thread; no error handling |

Simple rule

If you need to filter/sort/search a list of items, use Room. If you are storing simple settings, use DataStore.

11. Networking: Retrofit, Errors, Offline UX

Networking is where beginner apps become “real”. The critical skill is not making a request—it is handling reality: timeouts, offline mode, server errors, and partial failures.

Non-negotiable UX behaviors

- Loading state: show progress and avoid double-taps triggering duplicates.

- Error state: show a friendly message and a retry action.

- Offline behavior: tell the user what is happening; show cached data when possible.

- Logging: capture technical detail for debugging (not for users).

Networking checklist

- Show loading UI

- Handle offline and timeouts

- Handle non-2xx responses

- Show a friendly error + Retry

- Log technical detail for debugging12. Testing, Debugging, Performance & Accessibility

You do not need a huge test suite to benefit from testing. You need a repeatable safety net: a small set of unit tests for logic and a short regression checklist you always run before release.

Beginner testing stack

- Unit tests: ViewModel logic, state transitions, validation.

- UI tests (minimal): one critical journey (create item → view details → delete).

- Smoke tests: install release build on a device and click through key screens.

Performance habits that prevent later pain

- Test a release build occasionally (debug performance can mislead).

- Prefer stable list keys in LazyColumn and avoid heavy work in composables.

- Keep images optimized and avoid unnecessary recompositions.

Accessibility basics (easy wins)

- Add meaningful labels for icons and interactive elements.

- Ensure sufficient contrast and readable text sizes.

- Verify the app is usable with larger font settings.

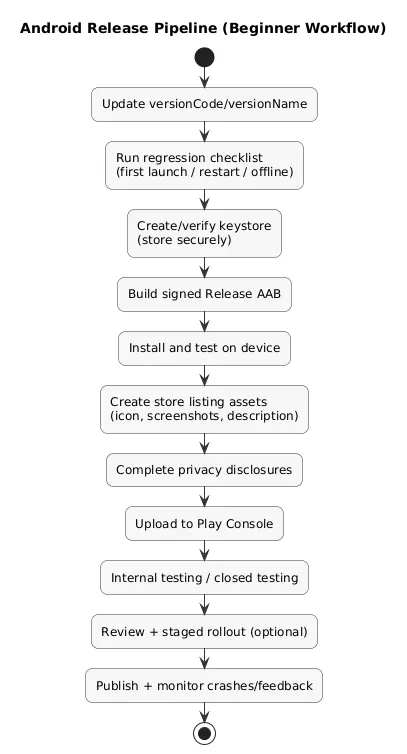

13. Release Checklist: Signing, AAB, Play Store

Shipping is a separate skill. A release build differs from debug, and store publishing introduces versioning and asset requirements. The best beginner strategy is to prepare release hygiene early.

Release pipeline (diagram)

Before you build release

- Versioning: bump versionCode/versionName consistently.

- Signing: create a keystore and store it securely (losing it is painful).

- Build: generate a release App Bundle (AAB) and test it on device.

- Privacy: ensure permissions and disclosures match real app behavior.

- Stability: run your regression list: first launch, restart, offline.

Fast win

Add basic crash reporting early so you learn what breaks on real devices—before reviews and users do.

14. FAQ: Android Basics

Is Kotlin enough to build production Android apps?

Yes. Kotlin is widely used in production and is a strong default for modern Android development.

Should I learn Compose first?

If you are starting in 2025, Compose is a practical default. Learn XML later when you need to maintain older apps.

Do I need MVVM for a first app?

You don’t need heavy architecture, but you do need boundaries. A ViewModel for state and repositories for data access are enough for most beginner apps.

How do I test across different devices?

Use emulator profiles for coverage, but validate key flows on at least one physical device—especially permissions and performance.

What is the easiest first Android app to build?

A notes or checklist app is ideal: multiple screens, local storage, and clear UI state—without requiring a complex backend.

Key Android terms (quick glossary)

- Android Studio

- The official IDE for Android development, including emulator tooling, profilers, and Compose previews.

- Kotlin

- A modern JVM language commonly used as the default for Android development.

- Jetpack Compose

- A declarative UI toolkit where the UI is rendered from state.

- ViewModel

- A state holder for UI logic that survives configuration changes.

- Flow

- A reactive stream type used to emit values over time (often for UI state).

- Gradle

- The build system that manages dependencies and produces app builds.

- AndroidManifest.xml

- Declares app metadata, components, permissions, and intent filters.

- Room

- A persistence library for structured local data storage with SQLite under the hood.

- DataStore

- A modern storage solution for preferences and small key-value data.

- Retrofit

- A popular HTTP client library pattern for defining API interfaces and networking calls.

Worth reading

Recommended guides from the category.