Data analysis with Python is not about writing “clever code”. It is about making datasets understandable, trustworthy, and decision-ready. In practice, that means you load data, validate schema, clean issues, transform fields, compute metrics, visualize patterns, and document assumptions.

This guide focuses on fundamentals you will use repeatedly: pandas for tabular data, NumPy for numeric work, and straightforward plotting for communicating results. The goal is a repeatable workflow you can apply to real datasets, not just toy examples.

Good analysis signal

If someone else can rerun your notebook from raw data to the same conclusions, your analysis is already above average.

Related guides

If you want the broader context, start with Data Science for Beginners. If your goal is employment and portfolio planning, follow How to Become a Data Scientist.

1. What Data Analysis with Python Is (And What It Is Not)

Data analysis turns raw data into insights you can defend. With Python, that typically includes:

- Loading data from files or databases,

- Profiling schema and data quality (fast checks first),

- Cleaning and typing columns,

- Transforming fields into analysis-ready features,

- Summarizing metrics by segment and time,

- Visualizing patterns clearly,

- Packaging outputs so others can rerun and trust them.

What it is not: skipping validation, eyeballing numbers, and trusting the first chart you produce. Most analysis errors come from silent issues like wrong types, duplicated rows, missing values, or joins that multiply data.

2. Setup: Python, Jupyter, and the Minimum Toolchain

You can do analysis in scripts, but notebooks are great for exploration. A minimal setup:

- Python 3.11+ (or 3.10+): stable ecosystem.

- Jupyter: Notebook or JupyterLab.

- pandas + NumPy: core data stack.

- matplotlib (+ seaborn optional): visualization.

Minimal install

pip install pandas numpy matplotlib seaborn jupyter3. The workflow overview (the repeatable pipeline)

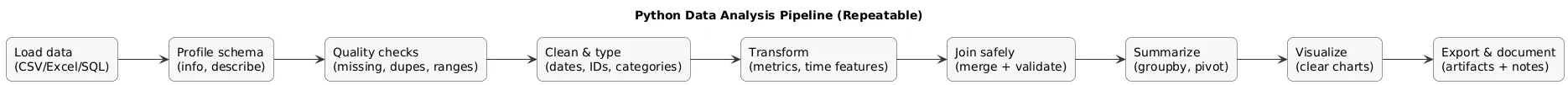

The biggest beginner upgrade is to stop thinking in isolated commands and start thinking in a pipeline: each step produces a clearer dataset and a clearer answer. If you do the steps in order, you will avoid most pitfalls.

Python analysis pipeline (diagram)

4. Step 1: Load Data (CSV, Excel, SQL)

Start by loading data into a DataFrame. Treat loading as part of data quality: specify encodings, separators, and types when needed.

import pandas as pd

# CSV

df = pd.read_csv("data/orders.csv")

# Excel

df_xlsx = pd.read_excel("data/orders.xlsx", sheet_name="Orders")

# SQL (example pattern)

# from sqlalchemy import create_engine

# engine = create_engine("postgresql+psycopg://user:pass@host:5432/db")

# df_sql = pd.read_sql("SELECT * FROM orders", engine)Load responsibly

If a column should be a date, parse it as a date. If an ID should be a string (leading zeros matter), force it to string early.

5. Step 2: First Look (Schema, Types, Quick Profiling)

Before cleaning or plotting, confirm what you actually imported: columns, types, missingness, and row counts. This is where you catch “numbers stored as text” and “dates stored as strings”.

df.shape

df.head(5)

df.info()

df.describe(include="all")

# Missing values per column (as %)

(df.isna().mean() * 100).sort_values(ascending=False).head(10)Common trap

Dates imported as strings and numeric columns imported as objects will produce misleading summaries and charts. Fix types early.

6. Step 2.5: Data quality checks (fast and practical)

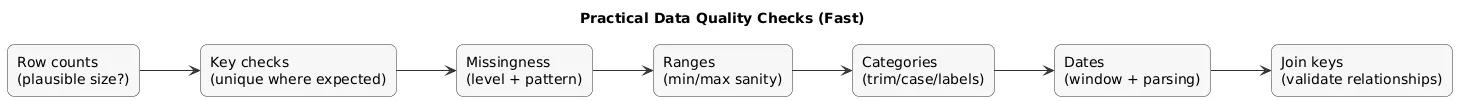

A small set of quality checks prevents most downstream mistakes. You do not need a heavy framework to start; you need consistency and a short checklist.

Data quality checks (diagram)

- Row counts: is the dataset size plausible?

- Key uniqueness: should an ID be unique? verify it.

- Missingness: how much is missing, and is it concentrated in specific segments?

- Ranges: negative revenue, impossible ages, dates outside expected windows.

- Category hygiene: whitespace/casing issues that create fake categories.

- Join safety: validate relationship types before merging.

# Example: uniqueness check

df["order_id"].isna().mean()

df["order_id"].nunique(), len(df)

# Example: suspicious negative values

df.loc[df["quantity"] < 0].head()7. Step 3: Clean Data (Missing Values, Duplicates, Types)

Cleaning is not “make it pretty”. It is: remove ambiguity and enforce rules. Typical tasks:

- Handle missing values: drop, impute, or keep with explicit meaning.

- Remove duplicates: especially after concatenation or merges.

- Fix types: numbers, dates, categories, IDs.

- Normalize values: consistent casing, trimming, standard labels.

# Remove exact duplicate rows

df = df.drop_duplicates()

# Convert date strings to datetime

df["order_date"] = pd.to_datetime(df["order_date"], errors="coerce")

# Ensure IDs stay as strings

df["customer_id"] = df["customer_id"].astype("string")

# Missing values strategy (simple example)

df["discount"] = df["discount"].fillna(0)Document decisions

Write a one-line comment for each important cleaning rule. Later you will not remember why you filled missing values with 0.

8. Step 4: Transform Data (Columns, Strings, Dates)

Transformations make the data analysis-ready: standard columns, create useful fields, and encode domain logic. This is where you create metrics like revenue, margins, and time features.

# Standardize column names

df.columns = [c.strip().lower().replace(" ", "_") for c in df.columns]

# Create a numeric metric

df["revenue"] = df["quantity"] * df["unit_price"]

# Extract year/month from a datetime column

df["year"] = df["order_date"].dt.year

df["month"] = df["order_date"].dt.to_period("M").astype("string")

# Clean strings

df["country"] = df["country"].astype("string").str.strip().str.title()Type discipline (beginner-friendly rule)

Treat IDs as strings, dates as datetime, and categories as category when repeated heavily. You will reduce bugs and improve performance.

9. Step 5: Summarize with groupby, pivot_table, and aggregations

Most analysis questions are aggregations. Use groupby for KPIs and segmentation, and pivot tables for reporting views.

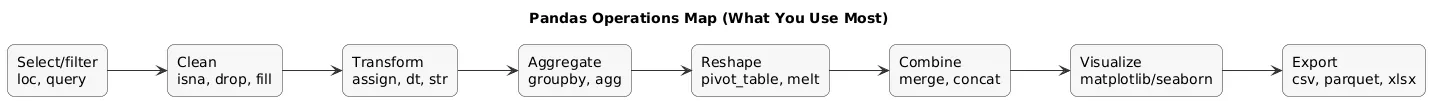

Common pandas operations map (diagram)

# Revenue by month

rev_by_month = (

df.groupby("month", as_index=False)["revenue"]

.sum()

.sort_values("month")

)

# Multi-metric summary by country

kpis_by_country = (

df.groupby("country")

.agg(

orders=("order_id", "nunique"),

customers=("customer_id", "nunique"),

revenue=("revenue", "sum"),

avg_order_value=("revenue", "mean"),

)

.sort_values("revenue", ascending=False)

)

# Pivot table example

pivot = pd.pivot_table(

df,

index="month",

columns="country",

values="revenue",

aggfunc="sum",

fill_value=0,

)Aggregation sanity check

Always validate totals. If the sum changes unexpectedly after a join or reshape, you likely introduced duplicated keys or many-to-many joins.

10. Step 6: Combine Datasets (merge, joins, keys)

Real analysis often needs multiple tables (orders, customers, products). Understand your keys: one-to-one, one-to-many, or many-to-many. Many-to-many merges are the #1 reason for inflated totals.

# Example: enrich orders with customer attributes

customers = pd.read_csv("data/customers.csv")

# validate="m:1" means: many orders to one customer

orders_enriched = df.merge(customers, on="customer_id", how="left", validate="m:1")Use validate

validate turns silent join mistakes into loud errors while you still have context. It is one of the most practical pandas habits you can build.

11. Performance basics (speed without cleverness)

Beginner performance wins are usually simple. Before rewriting code, check whether you can reduce work: fewer columns, fewer rows, more vectorization, and better types.

- Select only needed columns when loading (usecols) and before merges.

- Prefer vectorized operations over Python loops.

- Use category for repeated strings (country, status, channel).

- Be careful with apply: it is often slower than built-in pandas operations.

# Example: reduce memory for repeated strings

df["country"] = df["country"].astype("category")

# Example: avoid row-by-row loops (vectorized metric)

df["revenue"] = df["quantity"] * df["unit_price"]12. Step 7: EDA Workflow (Questions, Distributions, Outliers)

EDA works best when you write down questions first, then verify with summaries and plots. A simple workflow:

- Quality: missing values, duplicates, impossible values.

- Univariate: distributions, ranges, skew.

- Bivariate: relationships between key variables.

- Segmentation: by category, cohort, time.

- Outliers: decide whether they are errors or signal.

# Quick outlier scan (example thresholds)

df.loc[df["revenue"] < 0].head()

df["revenue"].quantile([0.5, 0.9, 0.95, 0.99])EDA mistake to avoid

Do not treat outliers automatically as “bad data”. Some outliers are your most valuable customers or rare but important events.

13. Step 8: Visualize Clearly (matplotlib + seaborn basics)

The goal of plotting is clarity, not decoration. Start simple: trend lines, histograms, and bar charts for categories. Tie each chart to a question and label it so it can stand alone in a report.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Line chart (revenue by month)

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 4))

plt.plot(rev_by_month["month"], rev_by_month["revenue"])

plt.xticks(rotation=45)

plt.title("Revenue by Month")

plt.xlabel("Month")

plt.ylabel("Revenue")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()Plot hygiene

Add titles, label axes, and sort categories. If a chart cannot be understood without explanation, it is not finished.

14. Step 9: Basic Statistics (sanity checks)

You do not need advanced statistics to deliver value. Basic checks help avoid false conclusions:

- Range checks: min/max for numeric fields.

- Counts: unique IDs, duplicates, missingness.

- Correlation: directional signal, not causation.

- Segment comparisons: medians often beat means when distributions are skewed.

# Correlation on numeric columns

numeric = df.select_dtypes(include=["number"])

corr = numeric.corr(numeric_only=True)

# Robust summary

numeric.describe(percentiles=[0.05, 0.5, 0.95]).T.head(10)Correlation caution

Correlation can guide questions, not prove answers. Always check for confounders (time, seasonality, segment mix).

15. Step 10: Make It Reproducible (notebooks, functions, exports)

Turn exploration into a repeatable pipeline: parameterize inputs, reuse cleaning functions, and export clean artifacts (cleaned data, tables, figures). Reproducibility is also an AdSense-friendly quality signal: it increases trust.

from pathlib import Path

import pandas as pd

OUTPUT = Path("out")

OUTPUT.mkdir(exist_ok=True)

def clean_orders(df: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame:

df = df.drop_duplicates().copy()

df["order_date"] = pd.to_datetime(df["order_date"], errors="coerce")

df["discount"] = df["discount"].fillna(0)

df["revenue"] = df["quantity"] * df["unit_price"]

return df

df_clean = clean_orders(df)

df_clean.to_csv(OUTPUT / "orders_clean.csv", index=False)Deliverable mindset

A strong outcome is a notebook that (1) loads raw inputs, (2) applies documented cleaning, (3) produces summary tables and figures, and (4) exports a clean dataset and a short conclusions section.

Export formats (quick guidance)

- CSV: universal, human-readable, larger files.

- Parquet: fast, compact, preserves types well (great for repeat analysis).

- Excel: stakeholder-friendly for small reports, but less reproducible.

16. Common Beginner Mistakes (And How to Avoid Them)

- Trusting types by default: objects everywhere. Fix: run df.info() and explicitly parse dates/IDs.

- Ignoring duplicates: inflated metrics. Fix: define what “duplicate” means (row vs key).

- Many-to-many merges: totals grow. Fix: use validate and check key uniqueness.

- Plotting unsorted categories: unreadable charts. Fix: sort by metric, limit top-N, label axes.

- No reproducibility: results cannot be rerun. Fix: functions for cleaning + exported artifacts.

17. Data Analysis Checklist

Use this as a quick pre-flight for most Python analyses:

- Inputs: sources listed (files, queries, extracts).

- Schema: columns and types validated (info()).

- Quality: missingness, duplicates, impossible values checked.

- Cleaning rules: documented and implemented in code.

- Joins: keys validated; totals sanity-checked.

- EDA: distributions, relationships, segments explored.

- Visuals: labeled, readable, tied to questions.

- Outputs: exported tables/figures + short conclusions section.

- Reproducible run: notebook runs top-to-bottom without manual edits.

Fast win

Add one cell early: “Assumptions + known limitations”. It prevents most misinterpretations when the notebook is shared.

18. FAQ: Python Data Analysis

What should I learn first: NumPy or pandas?

Start with pandas for DataFrames and common operations (filter, select, groupby, merge). Learn essential NumPy concepts as you need them.

How do I handle missing values correctly?

Measure missingness, then pick a strategy aligned with meaning: drop if safe, impute if justified, or keep missing as its own category when it carries signal. Document the rule.

How do I avoid wrong totals after merges?

Check uniqueness of merge keys, use validate in pandas merge, and compare totals before and after. Many-to-many merges are the most common cause of inflated metrics.

What plots should I start with in EDA?

Use histograms for distributions, bar charts for categorical summaries, and line charts for trends over time. Move to more complex plots only when they answer a specific question.

How do I share results with non-technical stakeholders?

Provide 2–4 charts with a short summary, definitions of metrics, and a brief methodology note. Avoid dumping raw tables without context.

Key data terms (quick glossary)

- DataFrame

- A tabular data structure in pandas with labeled columns and rows.

- EDA

- Exploratory data analysis: profiling quality, distributions, and relationships before decisions or modeling.

- Missingness

- The amount and pattern of missing values in a dataset; it can bias results.

- Groupby

- A pandas operation that groups data and applies aggregations to compute KPIs.

- Join / Merge

- Combining tables using keys; incorrect keys can duplicate data and inflate totals.

- Outlier

- A value far from the typical range; it can be an error or meaningful signal.

- Reproducibility

- The ability to rerun the analysis from raw inputs to the same outputs using the same code.

Worth reading

Recommended guides from the category.