Cloud networking is usually learned backwards: you deploy an app, it works in dev, then production breaks with “can’t connect” errors. The fix is rarely magical—nearly every networking issue reduces to one of three causes: addressing (CIDR/IPs), routing (where packets go), or firewall rules (what traffic is allowed).

This guide is written for app developers who need a practical working model: how VPCs, subnets, routes, gateways, and firewalls interact, plus how to troubleshoot quickly under pressure.

Fast mental model

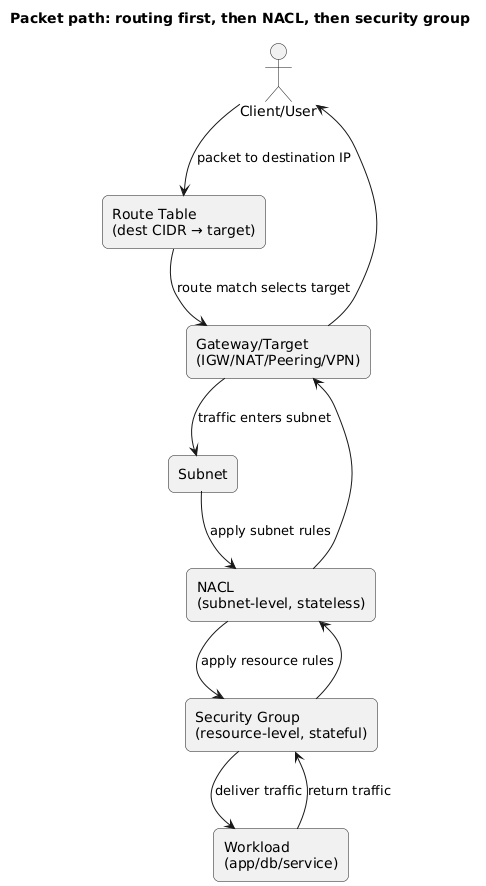

Packets follow this path: Subnet → Route table → Gateway/target, while firewalls (NACL then security group) decide what is allowed. If you can draw that for your app, you can debug most incidents in minutes.

1. The 5 building blocks of cloud networking

Cloud vendors use different names, but the primitives are consistent. If you master these five, the rest becomes implementation detail.

| Building block | What it is | What it controls | Common developer impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| VPC / VNet | Your private network boundary | IP range, isolation, attachments | “Are these services even in the same network?” |

| Subnet | Slice of the VPC IP range (often per AZ) | Where resources live | Public vs private design, HA patterns |

| Route table | Destination-to-target rules | Where packets go | “Why can’t it reach the internet/DB/other VPC?” |

| Gateways | Internet, NAT, VPN, peering targets | Network edges | Outbound access, inbound exposure, hybrid connectivity |

| Firewalls | Security groups and NACLs | Allowed ports/sources/destinations | Most common cause of “connection refused/timeout” |

Example: a real-world “it works locally” failure

Your app can call an external API from your laptop but times out in production. In cloud terms, that usually means: the app is in a private subnet without egress (missing NAT route), or outbound is blocked by security rules. Debugging starts at the route table, not the application code.

2. CIDR planning (avoid future pain)

CIDR blocks define how much “IP space” your network has. It sounds like paperwork until you try to connect networks (VPN, peering, multi-account setups) and discover your ranges overlap. Overlap is one of the hardest problems to fix later, so invest a few minutes up front.

Practical CIDR guidelines

- Use private ranges: 10.0.0.0/8, 172.16.0.0/12, or 192.168.0.0/16.

- Leave growth room: a /16 is common for production VPCs; smaller VPCs can work for isolated workloads.

- Avoid overlap: especially with corporate VPN ranges and other VPCs you may peer later.

- Plan per AZ: allocate subnets per availability zone for resilience (public + private).

- Reserve space for future tiers: you will likely add caches, queues, analytics, or internal tooling.

Why overlap hurts

Overlapping CIDRs make routing ambiguous. Even if your app “mostly works,” you’ll get bizarre partial failures when you add VPN, peering, or private endpoints. Fixing overlap often requires migrations and downtime.

3. VPCs and subnets: public vs private (what it really means)

A subnet is not inherently public or private. It becomes public or private based on its route table and how you assign public IPs.

-

Public subnet: has a route

0.0.0.0/0to an Internet Gateway (IGW). - Private subnet: does not route directly to an IGW. Outbound internet typically uses NAT.

Where to place common components

- Public: load balancers, NAT gateways, bastion host (if you still use one), public endpoints.

- Private (app): ECS/Kubernetes nodes, VM instances, internal services.

- Private (data): databases, caches, message brokers (when supported privately).

Example: the secure “default” for web apps

Users connect to a public load balancer. The load balancer forwards to app workloads in private subnets. Databases stay in private data subnets. Outbound internet for updates and third-party APIs goes via NAT. This minimizes direct exposure without complicating development.

4. Route tables: how traffic moves

Route tables are the “decision engine” of cloud networks. A route is essentially: destination CIDR → next hop target (local, IGW, NAT, peering, VPN, transit). Each subnet is associated with a route table (explicitly or via a default/main association).

Typical routes you’ll see

- Local route: the VPC CIDR routes internally (east-west traffic).

-

Default route:

0.0.0.0/0to IGW (public) or NAT (private egress). - Peering/transit: a route to another VPC CIDR via a peering or transit target.

- VPN/hybrid: routes to on-prem CIDRs via VPN/Direct Connect equivalents.

Debug shortcut

For any failed connection, write down: source subnet, destination IP/CIDR, expected next hop. Then confirm the subnet’s route table contains a matching destination. Routing errors are often visible instantly.

5. Internet gateway, NAT, and safe outbound access

Most apps need outbound internet (updates, package downloads, external APIs) but should not accept inbound internet traffic directly. That’s why the “private subnet + NAT” design is so common.

Internet Gateway (IGW)

- Provides a path between the VPC and the public internet when routes allow it.

- Typically attached once per VPC; public subnets route to it.

- Usually paired with load balancers and NAT gateways that sit in public subnets.

NAT (gateway or instance)

- Enables outbound internet for private subnets.

- Does not allow unsolicited inbound internet connections to private instances.

- Requires correct placement (public subnet) and correct routes (private subnet default route to NAT).

Most common NAT mistake

The private subnet points to NAT, but NAT cannot reach the internet (missing IGW route, wrong subnet association, or blocked outbound rules). Result: everything in private subnets times out on outbound calls.

Egress control (why security teams care)

Outbound access is a security boundary. If a workload is compromised, unrestricted outbound connectivity makes data exfiltration easier. Consider egress controls when your app handles sensitive data:

- Restrict outbound ports: allow only necessary destinations/ports where feasible.

- Prefer private endpoints: keep traffic to managed cloud services inside your VPC.

- Centralize egress: in larger environments, route outbound traffic through controlled appliances or gateways.

6. Firewalls: security groups vs network ACLs

Cloud “firewalls” usually exist at two layers: security groups (resource-level, stateful) and network ACLs (subnet-level, stateless). You can build secure systems with security groups alone; NACLs are typically added for coarse segmentation or compliance.

Security groups (SGs)

- Stateful: return traffic is automatically allowed.

- Attached to resources: instances, load balancers, managed services.

- Best practice: reference other SGs as sources instead of using broad CIDRs.

Network ACLs (NACLs)

- Stateless: you must allow both directions explicitly.

- Applied to subnets: affects everything in the subnet.

- Common pitfall: forgetting ephemeral ports causes intermittent failures and “random” timeouts.

Example: least-privilege rules (simple and effective)

Load Balancer SG: inbound 443 from internet;

outbound to App SG on 443/HTTP.

App SG: inbound only from Load Balancer SG;

outbound to DB SG on DB port (e.g., 5432).

DB SG: inbound only from App SG; no public inbound

rules.

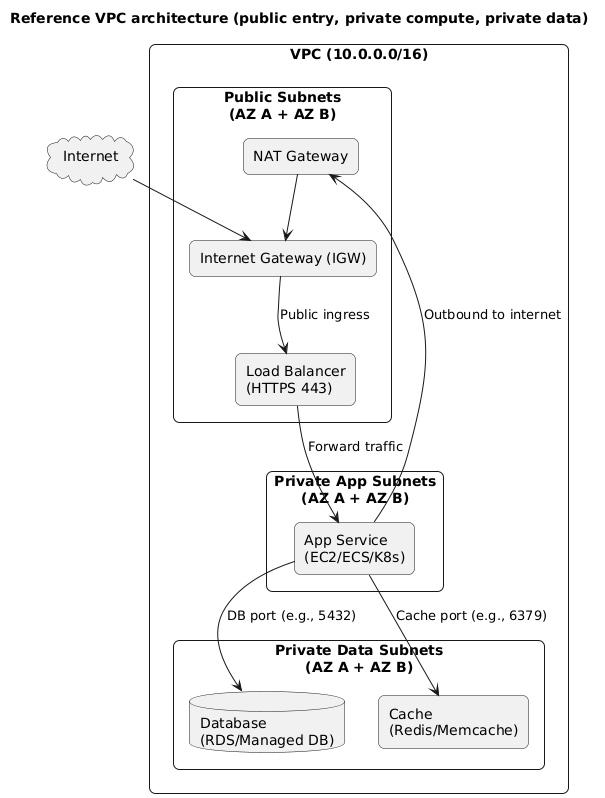

7. Reference architecture for a typical web app

If you are unsure where to start, this layout is the industry-standard baseline for production web applications. It balances security, simplicity, and operational clarity.

Reference VPC architecture (diagram)

Why this is a good default

- Reduced attack surface: app and DB are not directly internet-addressable.

- Clear network ownership: the load balancer is the public entry point; everything else is internal.

- Practical egress: private workloads can still access external dependencies through NAT.

- High availability ready: replicate subnets per AZ and spread workloads across them.

Implementation note

You can deploy this layout with VMs, containers, or Kubernetes. The networking concepts remain the same: public ingress to a controlled entry point, private compute, private data, controlled egress.

8. Private access to cloud services (endpoints / private link)

A common misconception is that “private subnet” automatically means “private traffic.” In reality, many cloud services are reached over public endpoints unless you configure private access. If your app relies heavily on managed services (object storage, secrets, container registries), private endpoints can significantly improve security and sometimes reliability.

When private endpoints help

- Security posture: keep traffic inside your VPC; reduce exposure to public internet paths.

- Policy enforcement: restrict access to services so only your VPC can reach them.

- Operational consistency: fewer variables (no NAT dependency for service traffic).

Example: removing NAT dependency for core services

If your workloads are in private subnets and they must pull images from a container registry or fetch secrets at boot, a NAT outage can prevent deployments. Private endpoints for those services keep the boot path inside the VPC, reducing “deployment fails because NAT is down” incidents.

9. Connecting networks: peering, transit, VPN

As systems grow, you often split environments (dev/stage/prod), teams, or services into multiple VPCs/accounts. At that point, you need a safe way to connect networks. The correct choice depends on scale and topology.

Options (high level)

- VPC peering: simple point-to-point connectivity between two VPCs (watch for CIDR overlap).

- Transit hub/gateway: hub-and-spoke model for many VPCs; simplifies routing at scale.

- VPN: connect to on-prem or to developer networks; good for admin access and hybrid connectivity.

Peering gotcha

Peering does not automatically make everything reachable. You still need correct routes on both sides and firewall rules that allow the traffic. “Peering exists” is not the same as “routes and security are correct.”

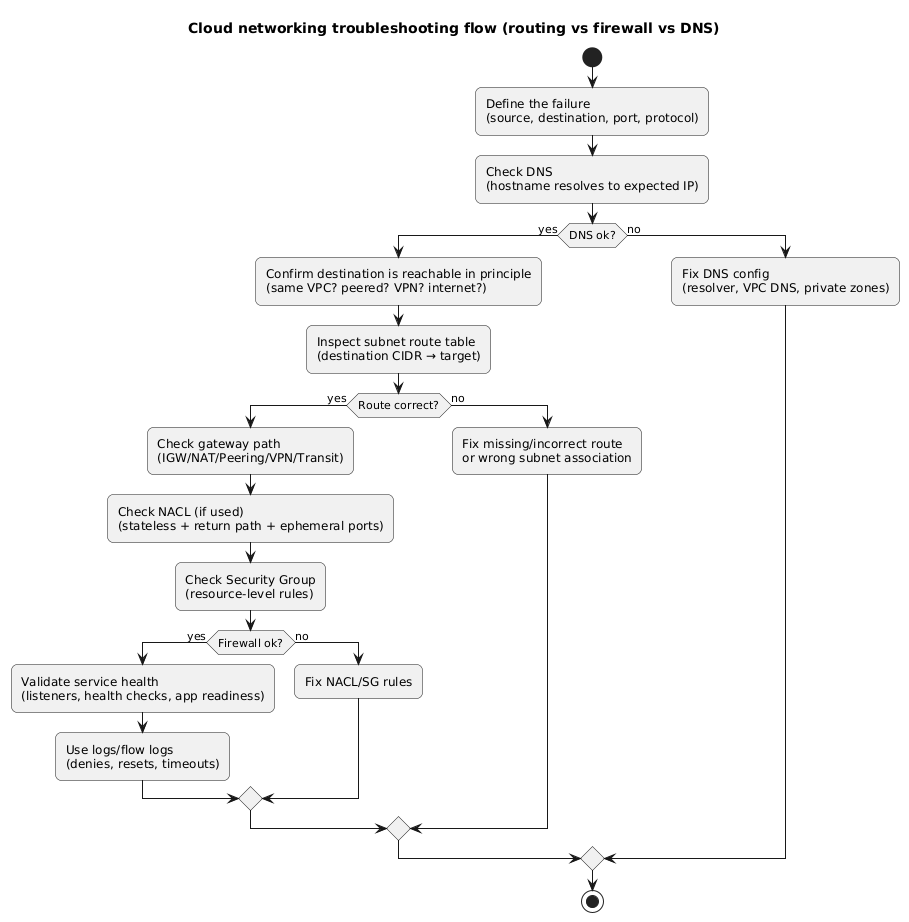

10. Troubleshooting: isolate routing vs firewall vs DNS

The fastest troubleshooting approach is to separate the problem into layers. DNS failures look different than routing failures, and routing failures look different than firewall denies. If you follow a consistent flow, you will avoid random guessing and “works after I changed five things” fixes.

Troubleshooting flow (diagram)

What to check first (common scenarios)

-

Private subnet cannot reach the internet: private

route table has

0.0.0.0/0→ NAT, NAT is in a public subnet, NAT subnet has0.0.0.0/0→ IGW, and outbound security rules allow egress. - App cannot reach database: DB security group allows inbound from App SG on the DB port, app subnet routes are local/peering-correct, and NACLs (if used) allow both directions.

- Load balancer says targets are unhealthy: security group allows inbound from LB to app port, app responds to health check path, health check timeout is reasonable, and the app is listening on the expected interface/port.

- Intermittent timeouts: NACL stateless rules missing ephemeral ports, connection tracking limits, or health check thresholds flapping under load.

One diagram to remember

Routing and firewall layers apply in order. If you understand which layer is blocking traffic, you can fix the right thing.

Routing vs firewall layers (diagram)

11. Deployment checklist (copy/paste)

Use this as a release gate

Treat network changes like production code. A single route or firewall rule can expose data or take your app offline. Use a checklist and require review for changes.

Design and addressing

- VPC CIDR chosen with growth room and no overlap with expected peer/VPN ranges.

- Subnets created per AZ (at least two AZs for production).

- Separate public subnets (LB/NAT) from private app subnets and private data subnets.

Routing

- Public subnets:

0.0.0.0/0→ Internet Gateway. -

Private app/data subnets:

0.0.0.0/0→ NAT (if outbound internet is required). - Peering/VPN/transit routes explicitly added on both sides where applicable.

- Route tables explicitly associated with the correct subnets (avoid accidental “main route table” usage).

Security

- Security groups follow least privilege; prefer SG-to-SG rules over broad CIDRs.

- Databases: no public inbound rules; inbound allowed only from app tier SG.

- NACLs (if used): rules are symmetric; ephemeral ports considered; denies documented.

- Admin access is restricted (VPN/SSO, audited) and not open to the internet.

Operations

- Health checks validated end-to-end (LB listeners, target groups, readiness endpoints).

- Network visibility enabled (flow logs and relevant gateway/load balancer metrics).

- Runbooks exist for: “no egress from private subnet,” “DB connectivity failure,” “targets unhealthy.”

- Rollback path documented (previous SG rules/route entries available and tested).

12. FAQ

Do I always need private subnets for production?

Not strictly, but they are a strong default for most internet-facing apps that handle user data. Private subnets reduce direct exposure and make it easier to enforce least privilege. Public-only designs can be appropriate for small, low-risk workloads, but treat them as an explicit trade-off.

Why does my app break only after moving into private subnets?

Private subnets change egress behavior. Outbound access may require NAT, and some managed services may still use public endpoints unless you configure private access. Check route tables, NAT placement, DNS settings, and outbound rules.

Security groups vs NACLs—what should I start with?

Start with security groups and least-privilege rules. Add NACLs when you need subnet-level segmentation, explicit denies, or compliance boundaries. If you add NACLs, ensure you understand stateless behavior and ephemeral ports.

Key terms (quick glossary)

- VPC / VNet

- Your isolated cloud network boundary where you control addressing, routing, and firewall attachments.

- Subnet

- A slice of a VPC CIDR, typically scoped to an availability zone, with an associated route table.

- Route table

- A set of rules mapping destination CIDRs to targets like local routing, IGW, NAT, peering, or VPN.

- Internet Gateway (IGW)

- The gateway that enables internet connectivity for subnets that route to it.

- NAT gateway

- Allows private subnets to initiate outbound internet connections without allowing unsolicited inbound traffic.

- Security group

- A stateful, resource-level firewall controlling allowed inbound and outbound connections.

- Network ACL (NACL)

- A stateless, subnet-level filter requiring explicit inbound and outbound rules.

Worth reading

Recommended guides from the category.