Synthetic training data for text tasks is popular for a simple reason: it solves the hardest bottleneck in applied NLP—getting enough labeled examples. With modern LLMs, you can generate thousands of candidates in minutes and use them to train (or fine-tune) models for classification, extraction, summarization, or instruction following.

The catch is that synthetic data is not “free accuracy.” It changes what your model sees during training. If the synthetic distribution is cleaner, more polite, more repetitive, or subtly wrong, your model will learn those properties—and that is where synthetic data backfires.

The honest promise of synthetic data

Synthetic data lets you shape the training distribution deliberately. If you can define correctness and validate it, synthetic data can be a multiplier. If you cannot validate it, synthetic data can become a confident way to teach your model the wrong thing—at scale.

1. What synthetic training data actually is (and what it is not)

“Synthetic training data” means examples that are not directly collected from real users or production logs. In practice, synthetic text datasets come from a few families:

- LLM-generated examples: prompts produce inputs, labels, or both (e.g., instruction-response pairs, labeled intents, structured JSON outputs).

- Template- or grammar-generated data: controlled generation with slots and rules, often high precision and great for narrow tasks.

- Pseudo-labeling: you label real unlabeled data using a model’s predictions (often with confidence thresholds), then train on those labels.

- Weak supervision: you apply heuristic rules (labeling functions) to create noisy labels at scale, then let the model learn a smoother decision boundary.

1.1 What synthetic data is not

- Not a substitute for evaluation: “reads well” is not a metric. You need correctness checks and protected, production-like evaluation sets.

- Not automatically privacy-safe: synthetic text can still contain personal data if prompts include it or if the generator memorized it. You must scan and govern it like any dataset.

- Not immune to distribution shift: if the generator writes cleaner text than your users, your model may fail on messy reality (typos, shorthand, mixed languages, quoted emails, logs).

2. When synthetic data works extremely well for text tasks

Synthetic data shines when the task has clear correctness criteria and when you can validate outputs with rules, schemas, or reference sources. In those situations you can scale generation, filter aggressively, and end up with a dataset that is both large and reliable.

2.1 Classification and routing tasks

Intent classification, topic labels, email routing, ticket triage, policy categorization—these often benefit because:

- labels are discrete and can be sanity-checked,

- you can balance class coverage (including rare intents),

- you can generate hard negatives (near-miss examples) deliberately.

A high-ROI pattern for routing

For each label, generate 5–10 “families” of examples: short queries, long explanations, slang/typos, multilingual variants, ambiguous cases, and adversarial near-misses. Then cap per-family volume to prevent one style from dominating.

2.2 Extraction to a schema (structured outputs)

If your model must extract fields into JSON (e.g.,

{"amount":..., "date":..., "merchant":...}), synthetic

data is often a win because you can validate examples mechanically:

- JSON parses,

- required keys exist,

- types match the schema,

- values match patterns (dates, currencies, IDs) and appear in text.

Structured extraction is one of the best use cases because correctness is measurable and automation-friendly.

2.3 Formatting, rewriting, and normalization

Tasks like “rewrite in a more formal tone,” “convert to bullet points,” “normalize addresses,” or “standardize product titles” are well-suited because they are transformations. You can validate outputs with:

- format checks,

- length constraints,

- presence/absence constraints (no new facts; preserve key entities),

- reference comparisons (semantic similarity with guardrails).

2.4 Summarization on controlled inputs (with grounding)

Summarization synthetic data is safer when it is grounded in a known input document and you enforce “no new facts.” If you generate both inputs and summaries from scratch, you risk training the model to sound convincing rather than accurate.

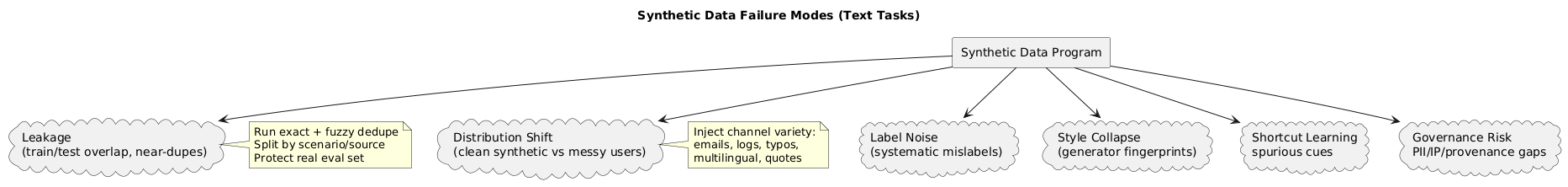

3. When it backfires: the common failure modes

Most synthetic-data failures are not mysterious model bugs. They are dataset distribution failures. Here are the patterns that show up in real deployments.

3.1 Distribution shift: “clean synthetic” vs messy production

LLM-generated text is often more grammatical, more complete, and more “on-topic” than real user text. If your training data becomes too clean, your model will struggle with:

- typos, shorthand, fragments, emojis, code-switching,

- quoted email threads, signatures, forwarded headers,

- copy-pasted logs, stack traces, and boilerplate,

- multi-intent messages that humans write naturally.

3.2 Label noise: scalable wrongness

If the generator or pseudo-labeler assigns the wrong label (or subtly wrong extraction), the model will learn a systematically wrong mapping. The impact is worse than random noise because it can be consistent and directional.

3.3 Style collapse and shortcut features

When synthetic data dominates, models can learn generator-specific style cues (phrasing, politeness markers, structure). Offline metrics may look fine while real-world generalization degrades.

3.4 Leakage: train/test overlap and benchmark contamination

Leakage happens when evaluation data overlaps (exactly or near-duplicate) with training. Synthetic pipelines amplify this risk because they tend to reuse patterns. If your test set is contaminated, you get inflated scores and production surprises.

3.5 Governance failures: privacy, IP, provenance

Synthetic does not mean “no compliance.” If prompts include sensitive data, or if the generator reproduces memorized text, your dataset can still contain PII or copyrighted passages. Treat synthetic datasets as governed assets with audit trails and versioning.

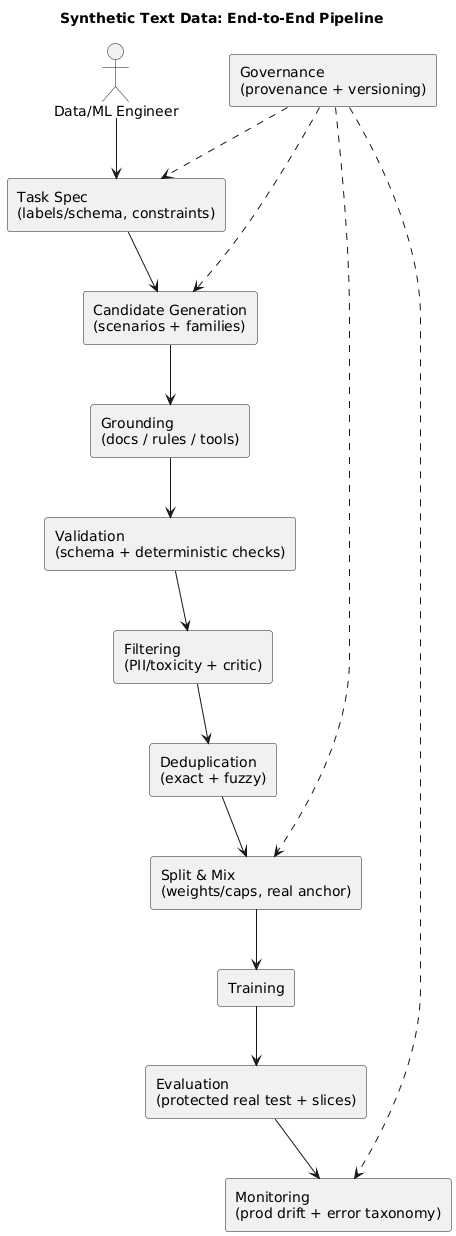

4. The end-to-end pipeline blueprint (diagram)

The most reliable teams treat synthetic data like any other production pipeline: inputs, transformations, quality gates, artifacts, and monitoring.

A practical baseline pipeline looks like this:

- Task spec: labels/schema, constraints, edge cases.

- Generation: scenario-first candidates (not only paraphrases).

- Grounding: docs/rules/tools so outputs are verifiable.

- Validation: schema checks, constraints, deterministic tests.

- Filtering: PII/toxicity + model critic + sampling review.

- Deduplication: exact + fuzzy across splits and sources.

- Mixing: ratios/weights/caps anchored on real data.

- Evaluation: protected real test set + slice metrics.

- Monitoring: production drift and error taxonomy.

- Governance: provenance, versioning, rollback plan.

5. Generation strategies that scale without collapsing quality

5.1 Start from a task spec that is brutally explicit

Before generation, define:

- Inputs: what users provide (length, channels, noise).

- Outputs: label set or schema, including “unknown.”

- Constraints: what must never happen (invent facts, include PII, exceed scope).

- Ambiguity policy: how to label ambiguous inputs (multi-label, needs-clarification, fallback class).

5.2 Scenario-first generation (then paraphrase)

For classification and extraction, generate by scenario, not by repeated paraphrase:

- Generate a scenario (what is happening and what the user wants).

- Generate multiple user utterances per scenario (short/long/messy/multilingual).

- Generate the target label/extraction based on the scenario rules.

Why scenario-first is better

Paraphrasing one sentence 200 times mostly changes surface form. Scenario-first changes the underlying situation, which creates deeper diversity and improves robustness.

5.3 Generate hard negatives intentionally

A reliable model must handle near-miss cases: messages that look similar but belong to a different label. Examples:

- refund request vs chargeback dispute,

- password reset vs account compromise,

- pricing question vs billing error,

- shipping delay vs wrong item delivered.

5.4 Vary formats and channels, not just wording

Production text arrives in many forms. Inject variety like:

- messages with quoted text, signatures, and forwarded headers,

- bullet lists and fragments,

- copied error logs or stack traces,

- emoji and shorthand,

- multiple languages in one message.

A prompt template you can reuse

Generate N labeled examples for {TASK}.

Rules:

- Labels: {LABELS} with short definitions.

- Include: typical, messy, rare, ambiguous, and hard-negative cases.

- Vary channel: chat, email, ticket subject, transcript, pasted notes.

- No PII. No real names, emails, phone numbers, addresses.

Output JSON lines:

{"text": "...", "label": "...", "notes": "why this label"} 6. Grounding: how to prevent “confident nonsense”

Grounding is the difference between synthetic data that trains competence and synthetic data that trains bluffing. “Grounding” means the target output can be verified against something other than the generator’s confidence.

6.1 Ground against a source document (QA and summarization)

- select a paragraph from a trusted corpus (docs, policy pages, KB),

- generate a question answerable from that paragraph,

- generate an answer that quotes or closely paraphrases the paragraph,

- verify every claim is supported by the paragraph.

6.2 Ground against rules (classification and extraction)

Define rules or constraints that can be automatically checked. Examples:

- if the label is Refund, the text must contain a refund-like request,

- if extraction outputs a date, it must exist in the input text,

- if output is a schema, it must validate and preserve key entities,

- if “unknown,” ensure the input truly lacks sufficient info.

7. Filtering and validation: turning 1M candidates into 50k good examples

Production-grade synthetic datasets are rarely “generate once and ship.” They are generated in bulk and then aggressively filtered.

7.1 Multi-stage quality gates (recommended)

- Format gate: JSON parses, keys exist, types match.

- Rule gate: label constraints satisfied; required evidence present.

- Safety gate: PII detection + toxicity screening.

- Consistency gate: self-consistency checks (e.g., regenerate label and compare).

- Critic gate: model-based reviewer grades realism and correctness.

- Sampling review: humans review stratified samples (especially edge cases).

Filtering is not optional

If you skip filtering, you are effectively training on unverified labels. The only question becomes: how fast do errors propagate into production?

7.2 Practical “critic” rubric (what to score)

- Correctness: is label/extraction objectively supported by the input?

- Realism: does the text look like real user behavior for that channel?

- Diversity: is this a duplicate pattern or a new family?

- Safety: any PII, sensitive attributes, or policy issues?

8. Deduplication and leakage prevention

Deduplication protects you from inflated metrics and brittle models. Do it in two layers:

- Exact dedupe: hash normalized text (lowercase, whitespace, punctuation normalization).

- Fuzzy dedupe: detect near-duplicates (MinHash / locality-sensitive hashing / embedding similarity).

8.1 Split correctly (avoid “near-duplicate across splits”)

Split by scenario or source whenever you can. If you randomly split at the example level, paraphrases of the same scenario can land in both train and test.

8.2 Protect evaluation sets

Keep a stable, protected real test set (and ideally a shadow “golden” production slice). Never generate synthetic data “from” the test set; never tune prompts against it; and run periodic overlap checks.

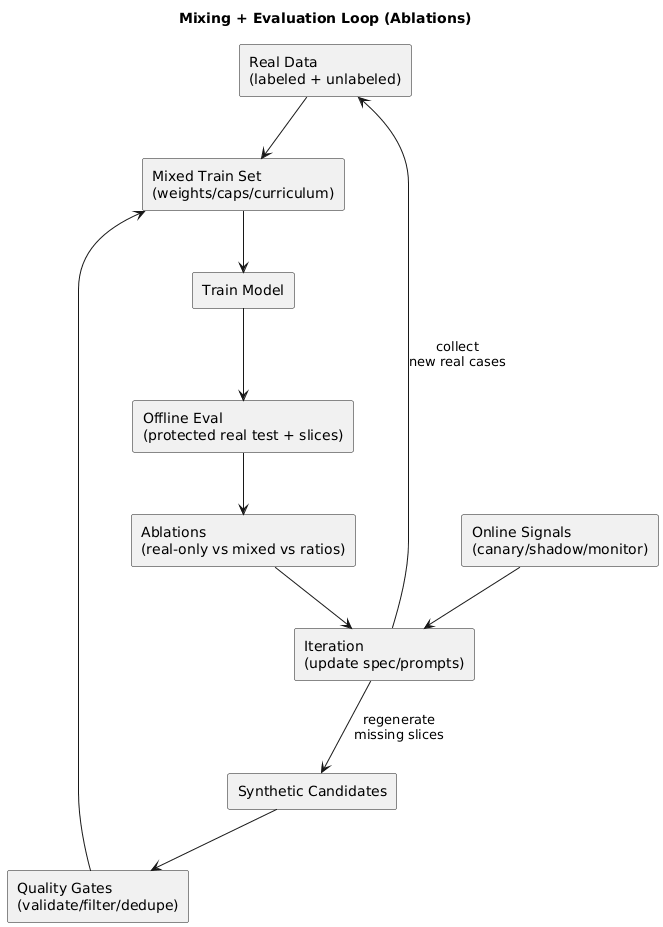

9. Mixing synthetic with real data: ratios, weighting, curriculum

The safest default is: real data anchors the model, and synthetic data fills coverage gaps (rare classes, hard negatives, formatting diversity).

9.1 Recommended mixing tactics

- Start small: add synthetic gradually and measure uplift with ablations.

- Use caps: cap synthetic per label/family to prevent style domination.

- Prefer weighting: keep real examples higher weight (or oversample real).

- Curriculum: start with clean, easy examples; later add messy and adversarial cases.

A practical rule of thumb

Smaller amounts of high-quality, well-filtered synthetic data usually beat massive synthetic-only datasets. If performance improves offline but worsens in production, suspect distribution shift and style collapse first.

10. Evaluation that actually predicts production outcomes

Synthetic pipelines often “overfit the lab.” To avoid shipping surprises, evaluation must be protected, slice-aware, and connected to real usage.

10.1 Build a stable real evaluation set

- collect real examples across channels and difficulty,

- label with clear guidelines (and measure annotator agreement),

- freeze a test set that is not used for prompt iteration.

10.2 Evaluate by slices, not only global averages

Track performance on slices like “typos,” “multilingual,” “long inputs,” “edge cases,” and “near-miss negatives.” Many regressions hide inside slices while global accuracy looks stable.

10.3 Tie offline to online

Where possible, validate with canaries, shadow deployments, and monitored error taxonomies. The goal is not just a higher score; the goal is fewer production failures per user session.

11. Governance: privacy, IP, provenance, auditability

Treat synthetic datasets like production assets. At minimum, store:

- Provenance: generator model/version, prompts, parameters, timestamp.

- Sources: which documents/rules were used for grounding.

- Filters: what checks were applied and thresholds.

- Versioning: dataset ID, changelog, and rollback path.

Dataset manifest template

{

"dataset_id": "synthetic_text_v12",

"created_at": "2026-01-02",

"generator": { "model": "LLM-X", "temperature": 0.4, "prompt_hash": "..." },

"grounding": ["kb_docs_v3", "ruleset_refund_v2"],

"filters": ["json_schema_v5", "pii_scan_v2", "toxicity_v1", "dedupe_minhash_v1"],

"mixing": { "real_weight": 2.0, "synthetic_cap_per_label": 20000 },

"notes": "Added hard negatives; expanded multilingual slice; tightened PII filter."

}12. Tooling and cost controls (practical ops)

- Batch generation: generate in batches and log metadata per batch.

- Prompt caching: reuse scenario scaffolds; vary surface forms cheaply.

- Two-pass approach: first generate candidates; second pass is verifier/critic.

- Sampling strategy: review stratified samples from each label/family, not random only.

- Cost guardrails: cap tokens, cap retries, and measure cost per accepted example.

13. Practical checklist (copy/paste)

- Define task spec: labels/schema, constraints, ambiguity policy.

- Design generation plan: scenarios + families + hard negatives.

- Choose grounding: docs/rules/tools so outputs are verifiable.

- Implement quality gates: format, rules, safety, consistency, critic.

- Deduplicate: exact + fuzzy; split by scenario/source when possible.

- Mix carefully: real anchors, synthetic caps/weights; track ablations.

- Evaluate properly: stable real test set + slice metrics + overlap checks.

- Monitor production: drift, error taxonomy, feedback loop.

- Govern dataset: provenance, versioning, audit, rollback.

14. Frequently Asked Questions

What text tasks benefit most from synthetic training data?

Synthetic data works best for constrained tasks with clear correctness criteria: intent classification, topic labeling, extraction to a schema, formatting and normalization, and instruction-following patterns grounded in known rules or documents.

Why does synthetic data sometimes reduce performance on real users?

Synthetic data can shift the training distribution toward the generator model’s writing style, introduce hallucinated labels, underrepresent edge cases, and create shortcut features. If it overwhelms real data or your evaluation set is contaminated, the model may look better offline while performing worse in production.

How should I mix synthetic and real data?

Start with a strong real validation set. Add synthetic data gradually, track uplift with ablations, and prefer weighting or caps per class. In many practical setups, a smaller amount of high-quality synthetic data paired with real examples performs better than a very large synthetic-only dataset.

What are the most important quality filters for synthetic text datasets?

Use multi-stage filtering: rule checks for format and schema validity, deduplication, contradiction checks (especially for QA), toxicity/PII scanning, and either human review or a model-based critic for label correctness and realism.

Can synthetic data help with privacy?

It can reduce reliance on raw user data, but it does not automatically guarantee privacy. Synthetic examples can still leak personal data if the generator saw it or if prompts include sensitive details. Treat synthetic datasets as potentially sensitive until you validate them with PII and memorization checks.

Key terms (quick glossary)

- Synthetic training data

- Artificially generated examples used to train or fine-tune a model. It may be template-generated, LLM-generated, pseudo-labeled, or weakly supervised.

- Pseudo-labeling

- Labeling real unlabeled data using a model’s predictions (often with confidence thresholds) and using those labels for training.

- Weak supervision

- Using heuristic rules or labeling functions to create noisy labels at scale, then training a model to learn beyond the rules.

- Grounding

- Ensuring outputs are verifiable against a source (documents, rules, constraints) rather than relying on the generator’s plausibility.

- Distribution shift

- A mismatch between the training data distribution and production data distribution—often the root cause of synthetic data regressions.

- Label noise

- Incorrect or inconsistent labels/targets that teach the model the wrong mapping, sometimes in systematic ways.

- Deduplication

- Removing exact and near-duplicate examples to prevent leakage across splits and to improve generalization.

- Hard negatives

- Near-miss examples that look similar to a class but should be labeled differently, used to prevent shortcut learning.

- Provenance

- Metadata about how an example was produced (generator model/version, prompts, sources, filters). Essential for auditing and rollback.

Worth reading

Recommended guides from the category.