Human-in-the-loop (HITL) review queues are the safety net and quality engine for AI systems in production. Instead of letting every output ship automatically, you route a targeted subset to humans using explicit rules: risk signals, low confidence, policy flags, validator failures, and escalation triggers.

The goal is not “add humans everywhere.” The goal is operational reliability: reduce defects and policy violations while using feedback to steadily shrink manual volume over time.

A useful framing

Treat HITL like an SRE practice for AI quality: define thresholds, route intelligently, measure throughput and escapes, and maintain a runbook for incidents (spikes, regressions, policy changes).

1. What HITL is (and what it is not)

- HITL is a controlled workflow that routes specific AI outputs to people based on measurable triggers.

- HITL is an improvement loop: decisions become signals to improve prompts, validators, routing, evaluation, and training.

- HITL is not “humans reviewing everything forever.” If queue volume never decreases, you likely lack good feedback plumbing.

2. Why Human-in-the-Loop exists

HITL is justified when mistakes are costly. Common reasons:

- High stakes: legal, medical, financial, privacy, and security risk.

- Uncertainty: low confidence, conflicting evidence, or thin context.

- Policy boundaries: content safety requirements, compliance, internal rules.

- Brand and quality: tone, completeness, and formatting must meet a standard.

- Novelty: new product feature, new domain, new market, or rapidly changing knowledge.

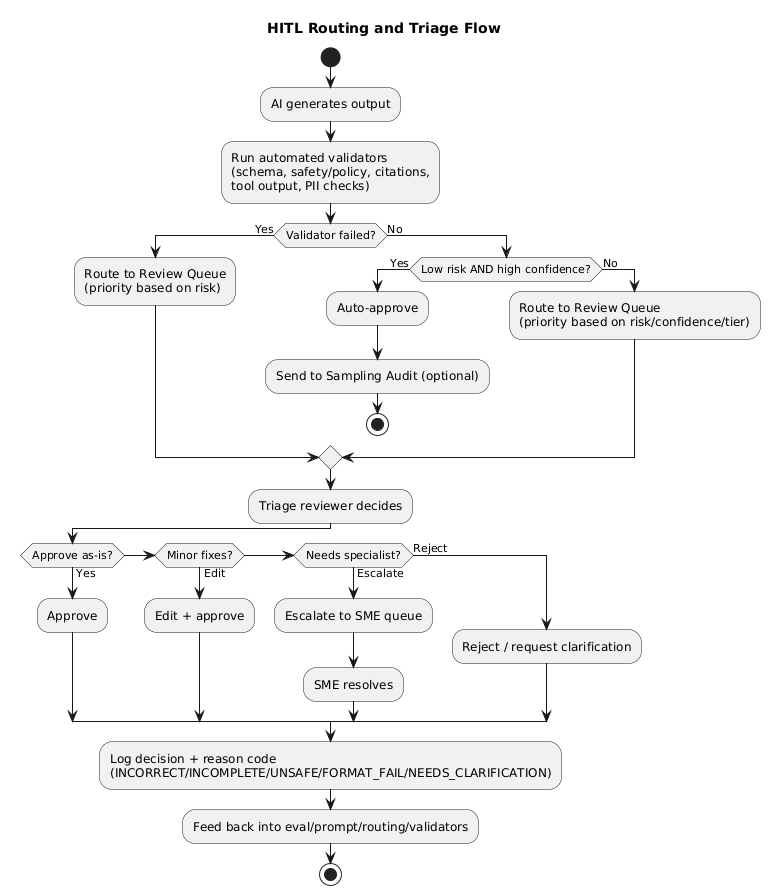

3. Routing rules: what goes to review

Routing is where most HITL systems succeed or fail. If your rules are vague, you’ll either review everything (cost blowup) or miss dangerous cases (risk blowup). Good routing rules are explicit, testable, and tied to outcomes.

3.1 Common routing triggers (practical list)

- Confidence gating: score below threshold → review (or abstain + review).

- Validator failure: JSON/schema invalid, citations missing, tool output malformed, forbidden content detected.

- Policy flags: regulated domains, sensitive categories, or policy keywords.

- Customer tier: stricter review for enterprise, high-value, or sensitive accounts.

- Novelty: new intents, unknown categories, new locales/languages, or “out-of-distribution” signals.

- Escalation triggers: user complaint, repeated retries, tool timeouts, or anomaly spikes.

3.2 A simple risk taxonomy (helps routing decisions)

| Risk level | Typical domains | Default handling | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | summaries, drafting, formatting, internal notes | auto-approve + sampling audit | minimise cost, monitor escapes |

| Medium | customer support replies, enterprise assistants, recommendations | confidence gating + validators + selective review | reduce defects and rework |

| High | privacy/security sensitive, regulated categories, high-liability actions | default-to-review + specialist escalation | prevent harmful outputs |

Routing failure mode

“Confidence” is not the same as “correctness.” Treat confidence as one signal among many (validators, policy flags, novelty, customer tier, and domain risk).

4. Queue design patterns that scale

Queue design should reduce context switching, keep decisions consistent, and make SLAs achievable.

- Single queue + priority lanes: easiest to start; use P0/P1/P2 lanes and strict SLA definitions.

- Specialist queues: route to SMEs (legal/security/finance) only when triggers fire.

- Two-stage review: fast triage first, deep review for a subset (prevents long-tail backlog).

- Batch review: group similar items (same template/category) to reduce reviewer overhead.

- Time-boxed review: “best effort” tiers where reviewer edits are limited by policy (cost control).

4.1 Queue states you should explicitly model

- New → In review → Approved / Edited / Rejected

- Escalated (specialist) → Resolved

- Needs clarification (blocked) → user/system request for additional context

- Expired (SLA missed / no longer relevant) with reason logged

5. Roles, escalation, and decision authority

Clear roles prevent inconsistent outcomes and reduce rework. A practical minimum set:

- Triage reviewer: quick approve/reject/escalate decisions, minimal edits.

- Quality reviewer: edits for correctness, completeness, tone, and format compliance.

- Specialist (SME): approves sensitive categories and high-risk outcomes.

- Queue lead: owns SLAs, backlog health, staffing, policy updates, and calibration sessions.

Escalation rule of thumb

If a reviewer needs to “invent policy” to decide, that is a specialist escalation. Reviewers should apply rules, not create them on the fly.

6. Rubrics and decision codes (templates)

Rubrics make decisions consistent. Decision codes make feedback loops possible. You want both.

6.1 Example rubric dimensions (score 1–5)

- Correctness: factual accuracy, no contradictions, appropriate uncertainty.

- Completeness: meets the user intent, covers required steps/constraints.

- Policy compliance: no disallowed content, safe phrasing, required disclaimers.

- Format quality: schema valid, citations present when required, tool outputs parseable.

- Clarity: readable, actionable, minimal ambiguity.

6.2 Decision codes (use these as structured labels)

| Code | Meaning | What it typically fixes |

|---|---|---|

| INCORRECT | Factual or logical error | prompt constraints, retrieval, eval set gaps |

| INCOMPLETE | Missing steps/constraints | prompt structure, checklist injection |

| UNSAFE | Policy violation or risky guidance | policy rules, guardrails, escalation routes |

| FORMAT_FAIL | Schema/JSON/tool output invalid | validators, tool specs, structured prompting |

| NEEDS_CLARIFICATION | Ambiguous request / missing context | better clarifying questions, UX changes |

7. SLAs, prioritization, and backlog control

Define SLAs that match your product expectations. At minimum track: time-to-first-review and time-to-resolution.

7.1 A simple priority model

- P0: safety, legal, security, or major customer impact (fastest SLA)

- P1: customer-facing quality issues (standard SLA)

- P2: internal content, low risk (best-effort + sampling)

7.2 Backlog control levers

- Reduce intake: tighten routing, fix validators, raise thresholds for low-risk areas.

- Increase throughput: staffing, batching, better reviewer tooling, shortcuts/templates.

- Reduce time per item: two-stage triage, time-box edits, make “reject with reason” acceptable.

- Prevent spikes: release gates and kill switch if defect rates jump.

Hidden backlog killer

If reviewers must write long free-form explanations, you will slow throughput and lose consistency. Use structured decision codes and short notes, not essays.

8. Sampling, audits, QA, and reviewer calibration

Even auto-approved outputs require oversight. Sampling is how you measure the “escape rate” and catch drift early.

- Random sampling: a baseline health signal.

- Risk-based sampling: oversample sensitive domains and new features.

- Double review: measure reviewer agreement and consistency.

- Calibration sessions: align on examples, update rubric interpretation, reduce variance.

- Audit trails: store decisions and artifacts for debugging and compliance.

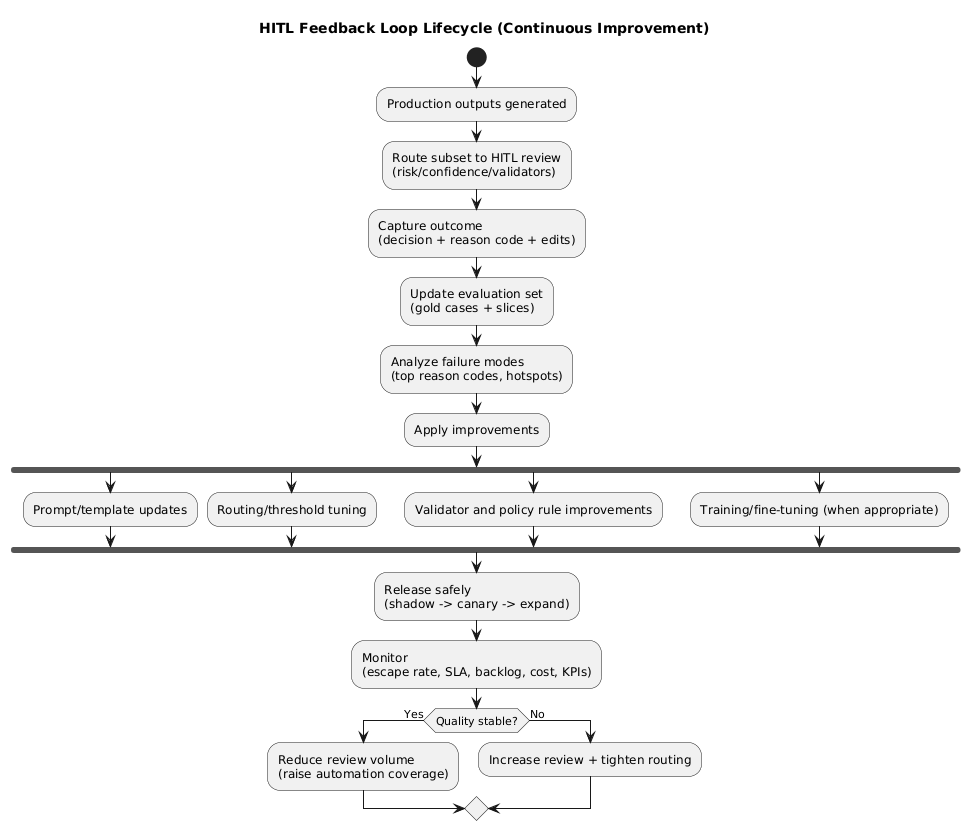

9. Feedback loops into prompts, rules, and training

HITL becomes a compounding advantage only when review outcomes are used to improve the system. The minimum viable loop is: decision + reason code → evaluation set → prompt/validator/routing change.

9.1 What to feed back (practical)

- Edits: the corrected output (when useful and safe to store).

- Reason codes: structured labels to quantify failure modes.

- Context: route triggers, validator failures, tool errors, and slice metadata (locale/tier).

- Outcome signals: user satisfaction, complaints, re-open rates, downstream KPIs.

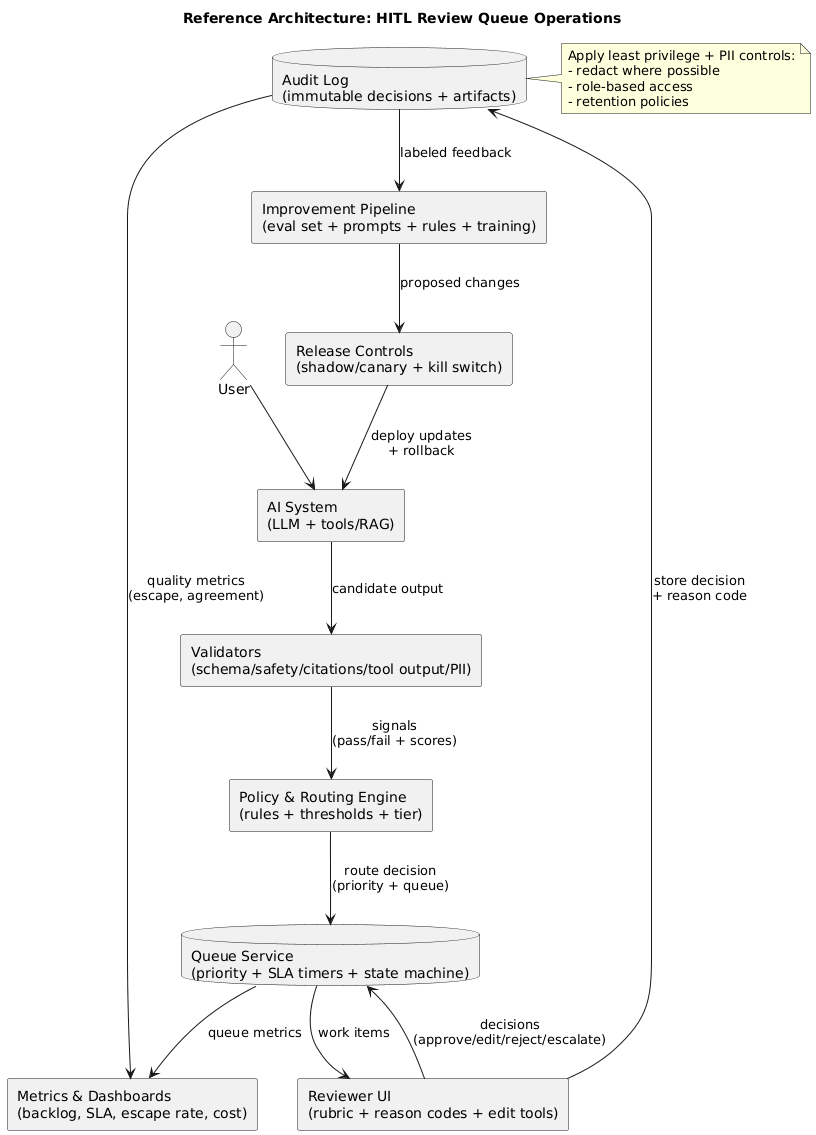

10. Reference architecture (implementation blueprint)

A production-ready HITL setup typically includes:

- Validators: schema checks, safety/policy classifiers, tool output validators.

- Policy engine: explicit routing rules and escalation triggers.

- Queue service: priorities, assignments, state machine, and SLA timers.

- Reviewer UI: rubric, decision codes, suggested edits, and short reason notes.

- Audit log: immutable record of decisions and artifacts (with PII controls).

- Metrics: throughput, backlog, SLA compliance, escape rate, agreement rate, cost per item.

- Feedback pipeline: reviewed items flow into evaluation, prompt/rules, and training as appropriate.

11. Cost control and scaling strategy

HITL cost is dominated by review volume and time-per-item. Scaling without control can be expensive, so build cost levers into the design from day one.

11.1 Practical cost levers

- Reduce volume: stronger validators + better prompts + stricter routing for only high-impact cases.

- Reduce time-per-item: batching, templates, and two-stage triage.

- Use sampling: audit low-risk automation rather than reviewing everything.

- Separate “approve” from “edit”: editing is slower; reserve it for cases where it materially matters.

- Measure ROI by tier: not all reviews have equal impact (prioritize high-value slices).

12. Copy/paste checklist

- Routing: confidence + validators + policy triggers + novelty signals

- Queue design: priorities (P0/P1/P2), explicit states, escalation path to SMEs

- Rubric: correctness, completeness, policy compliance, format quality, clarity

- Decision codes: INCORRECT / INCOMPLETE / UNSAFE / FORMAT_FAIL / NEEDS_CLARIFICATION

- SLAs: time-to-first-review + time-to-resolution + breach handling

- QA: random + risk-based sampling, double review, calibration sessions

- Security: PII handling, least privilege, audit logs, separation of duties

- Feedback: reviewed cases flow into eval sets and prompt/validator/routing improvements

- Kill switch: pause auto-approval when escape rate spikes

- Dashboards: backlog, throughput, SLA, escape rate, agreement rate, cost per item

13. Frequently Asked Questions

What does human-in-the-loop mean for AI systems?

Human-in-the-loop (HITL) means people review, approve, or correct selected AI outputs before they reach users. Routing is typically triggered by risk, uncertainty, or policy rules.

When should AI outputs be routed to a review queue?

Route outputs when the cost of a mistake is high (legal, medical, financial, privacy), when confidence is low, when policy-sensitive topics appear, or when automated validators fail (format, citations, tool schema).

How do you prevent review queues from becoming a bottleneck?

Use clear routing rules, prioritization and SLAs, automation for low-risk cases, sampling for audits, and continuous tuning of thresholds and validators. Track backlog and throughput so staffing matches demand.

What metrics matter for HITL review operations?

Track review volume, time-to-first-review, time-to-resolution, backlog size, approve/edit/reject rates, defect escape rate, reviewer agreement, and the impact of fixes on downstream quality and cost.

How should reviewer decisions feed back into the AI system?

Capture structured decision codes and edits, then use them to improve prompts, routing rules, validators, evaluation datasets, and training (where appropriate). The goal is to reduce future review volume while improving safety and quality.

What is the most important artifact to store from a review?

Store the final decision and a structured reason code (plus the edited output when relevant). Without reason codes, you cannot build reliable feedback loops or target improvements effectively.

Key terms (quick glossary)

- Human-in-the-loop (HITL)

- A workflow where humans review, approve, or correct selected AI outputs before release.

- Confidence gating

- Routing logic that sends low-confidence outputs to review or forces abstention.

- Validator

- An automated check (schema, safety, citations, tool output) used to block or route outputs.

- Triage

- Rapid classification to approve, reject, edit, or escalate items based on rules.

- Decision code

- A structured label explaining why an item was edited, rejected, or escalated.

- SLA

- Service-level agreement for time-to-first-review and time-to-resolution.

- Defect escape rate

- The rate at which harmful or incorrect outputs bypass review and reach users.

Worth reading

Recommended guides from the category.